|

|

Barry R. Taylor Random Cool Stuff This is a page for biologically interesting pictures or stories I come across from time to time.

Ruminating on Rodin: I'm pondering the meaning of The Thinker (Le Penseur), Paris, 2009. At least I'm keeping my clothes on. |

|

|

|

|

|

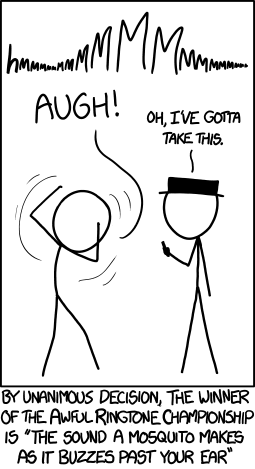

Visit xkcd.com (example on left), possibly the cleverest, funniest, weirdest cartoon anywhere on the web. Some of my favourites: |

|

|

|

Orchids With Attitude | |

|

There are three Phalaenopsis orchids in my house. The orchids bloom, or not, according to their whim. I give them a little water and a little sunshine and hope for the best. At the time of writing, the trio are neatly illustrating three distinct attitudes toward flowering. The first plant, call him White Pot, is pretty much with the program. It was blooming when I bought it, and after a decent period of rest it is blooming again. It used the interim to replace a few leaves and extend some aerial roots – a growth habit rather more effective in humid rainforest than in my dry livingroom. White Pot understands the life cycle of an orchid and follows it without much reflection. A reliable, unremarkable fellow. |

|

|

The second plant, Old One, is ensconced in a wicker plant stand like an old man glowering from his rocking chair, so deeply embedded with the other plants around it that I don’t know how to move it. Some of its aerial roots actually pass through the lattice of the wicker. Old One is blooming now, in a long peduncle of eye-catching blue flowers, none of which is really visible because Old One insists on projecting its flowers toward the window. Maybe it realizes in some botanical, biochemical way, that pollination is the ultimate point of the exercise and it should be directing its efforts “where the bees are”. Or maybe, like Narcissus gazing at his face in a pool, it is simply in love with its own reflection in the window. |

|

|

The third plant, Rooty, is of an entirely different disposition. Rooty wants nothing to do with this whole business of flowering, which it apparently considers gaudy and licentious. It bloomed in the store as a sort of contractual obligation, but hasn’t budged a bud since. Rooty sees the true measure of an orchid not in flowers but in roots, which it produces with energy and dedication. Roots are the source of sustenance, Rooty is saying, the conduits of water and nutrients that every plant needs. Roots make a plant strong. Flowers are for wimps. Thus my three orchids encapsulate three philosophies toward societal expectations: conform, rebel, or go your own way. I water them all regardless. |

|

|

| |

|

Puddling Swallowtails

Puddling is a social occasion. When one butterfly discovers a good spot for puddling (the soil must be neither too dry nor too wet) other butterflies passing by will join him. Much depends on the judgment of that first butterfly. Less appealing substrata such as rotting flesh and manure may also provide the minerals that puddling butterflies need. The butterflies in the picture lack blue coloration at the lower end of the wings, which means they are all male. Female butterflies seldom puddle. They don’t need to do so because the males deliver nutrients and minerals to them as part of a “nuptial gift”. The spermatophore transferred during mating contains sperm as well as nutrients and minerals to help the female lay healthy eggs. It’s the wedding night and child support combined. So these male butterflies puddling along the riverside are not gathering minerals for themselves – adult butterflies live for only a few weeks and do not grow – but for the next generation. Every swallowtail butterfly carries about a few grains of salt inherited from its father. | |

|

|

A Gaggle of Grosbeaks Evening Grosbeaks, Cocothraustes vespertinus,

are bright coloured birds

that occasionally visit our winter bird feeder.

Their gaudy plumage brings a flutter of colour to grey December days. When I mentioned to my

ornithologist colleague Randy Lauff, how pleased I was that a half dozen grosbeaks were hanging

around our feeder, he told me that grosbeaks were sometimes considered nuisance birds because they swarmed feeders

and drove the other birds away. I found that history surprising; yet within a week Randy’s

warning proved prophetic.

Take a look at this one-minute video. Be careful what you wish for. |

|

| |

|

Mushrooms and Memory

Recently I noticed these mushrooms fruiting out of one of the old posts, which are finally succumbing to the patient assault of the decomposers. The black spots on the post are blobs of creosote. Looking at the mushrooms, I was reminded of a line from a poem I had long forgotten, which refers to “the hollow tocsins of decay”. A tocsin is a warning bell, or here a funeral bell, but it is pronounced identically with toxin, a poison. This is an interesting match because here the toxin in the wood, the creosote, is in fact preventing the decay, or at least slowing it down. And the wood itself is becoming hollow, in the literal sense, because the fungus, unable to attack the oil-coated exterior of the posts, is instead slowly breaking them down from the inside. When the mushrooms have finished their work and the posts are nothing but creosote-soaked shells, won’t they then be “hollow toxins of decay”? There is an important codicil to this story. In 1985, when I was finishing my Ph.D., and presumably horses were lazing in the paddock, I went looking for poetry that referenced decomposition, to give my own thesis about leaf litter in forests a bit of cachet. That search led me to the poem about the hollow tocsins of decay, which I thought was by Shelley but apparently isn’t because it is likely that the line doesn’t exist. Or at least it doesn’t exist anywhere outside my head. I have searched exhaustively for the source of that line, using on-line search engines that didn’t even exist in 1985, along with more conventional forays through collections of famous poetry, of which, perplexingly, I have several. I cannot find it anywhere. I conclude that the line in my head was a trick of the memory: the residuum, after four decades of decay, of a different poem that contained the word “tocsin”, the rarity of which made it stick in my mind. Like the posts of the paddock, the “tocsin” has preserved the shell of a memory, but time has decomposed the interior into an empty hollow. | |

|

|

|

The Woodpecker and the Swallows | |

|

A friend gave me a copy of Aesop’s Fables, rendered in verse

by an English poet and entrepreneur named John Ogilby

in 1651. These classic stories use anthropomorphic animals to illustrate

lessons about how to live a good

life, or at least how to survive the treacherous jungle of human society. Taking my cue from Aesop (who, it

turns out, probably did not write the Fables so much as write them down), I have created my own fable, based

on a brief interaction among three birds in my front yard.

One June evening my spouse and I were having dinner on the screened front porch when a pileated woodpecker arrived. These big, flamboyantly dressed birds are an uncommon but welcome site around our house. This one landed on the ugly utility pole in front of the house. Why there is an ugly utility pole in front of the house, in full view from anywhere, rather than discreetly behind the house, is a mystery for another day. |

A pileated woodpecker, unintentionally the villain of the piece. |

|

The woodpecker landed near the top of the pole and beak-whacked the wood a few times, like a drummer testing a new snare. Evidently deciding the wood was too hard, he worked his way systematically down the pole, pecking from time to time, until he was no more than a metre from the bottom. He seemed to like it there. Perhaps he had discovered the carpenter ants. What the woodpecker did not know, or care to notice, was that a bird box nailed to this ugly utility pole was occupied by a pair of tree swallows, busily raising a brood of young. Perhaps the birds saw the woodpecker as a threat; perhaps they just didn’t want all that obnoxious noise around the kids. Either way, the bird inside popped out the hole and began harassing the woodpecker without relent, swooping and diving and filling the air with avian energy as only swallows can. The larger bird took this all in stride, at first. Every time the swallow dive-bombed, the woodpecker simply moved to the other side of the pole. It carried on pecking. There were ants to be had. Soon, however, the swallow was joined by its mate, and the two of them laid into the woodpecker with manic fury, not to mention a great deal of high-pitched chirping. They drove the woodpecker round and round the pole until eventually, apparently deciding these little birds were insane, it flew off across the yard into the forest. The swallows chased it until it was far away from their precious nest. |

|

|

Moral: Knocking about is all very well, but do keep it quiet where other folk dwell. |

|

|

| |

A Rumination on Rarity |

Why are some plants rare while others are common? The standard explanation for rare species is that they have become habitat specialists to avoid competition. Rather than fight it out, toothed leaf and clawed sepal, with their faster-growing neighbours, these species have retreated over evolutionary time to the fringes of society, where they can survive unperturbed. Uncommon species tend to be found in uncommon places: rock outcroppings, acid bogs, calcareous soil, heavy shade. Survival for these species becomes elemental: plant against nature rather than plant against plant. Natural selection, in its blindly effective way, has equipped these outcasts to acquire the resources they need in places that are reluctant to supply them. I dislike the appellation of rare plants as poor competitors – it makes them sound like losers. Some rare species are in fact at the end of their evolutionary tether; these can no longer compete against new arrivals, or in a landscape or climate that has changed since they were a younger species. But specialist plants are as competitive as anyone else within their habitat, and better adapted to it, which is why they grow there when everyone else can’t. |

|

|

These species have sacrificed the potential for rapid growth and heavy reproduction in richer lands for a slower but untrammelled life in their specialist habitat. They are the monks in the monastery, not the merchants in the village. Being rare is a secondary condition, the consequence of a non-competitive lifestyle. But can rarity itself be an evolved character? That is, can natural selection push a plant toward being uncommon because low numbers are of themselves conducive to survival? Plants in low densities may go unnoticed by consumers. Once a plant population reaches a certain density, generalist predators may begin to include it in their diet because its frequency makes searching for it worthwhile. Larger populations are likely to support more specialist parasites and diseases. Remaining rare and flying beneath the consumer radar could therefore be a successful life-history strategy. Call it strategic rarity. |

|

|

Would these mechanisms obtain? Are there rare species which have been shaped by evolution to maximize long-term fitness by sacrificing short-term fitness? Or would individual plants producing more offspring displace those producing fewer, even if the consequence of the greater fecundity were more consumer stress on everybody? D. O. Hessen and B. Walseng (2008, Freshwater Biology 53:2026-2035), clearly with too much time on their hands, scored presence of all 130 zooplankton species in 2467 Norwegian lakes. Most species were rare: 65% were found in fewer than 10% of localities, and any given site contained only 14 species on average. Significantly, while many rare species were early colonizers, quickly displaced, or habitat specialists, a substantial number appeared to be rare by nature. These species occurred only in a small number of lakes, or within a confined geographic area, and were never abundant anywhere. These species had apparently evolved to be rare. Most communities comprise relatively few common species and a long tail of increasingly rare species. Commonness is the uncommon condition. Maybe in our exploration of rarity we are asking the wrong question. Instead of wondering why some species are rare, perhaps we should be asking why all species aren't rare. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

A Tangled Bank | |

|

| |

|

A patch of hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula) and meadow-rue (Thalictrum pubescens) growing among other woodland herbs on the bank of Polsons Brook, Antigonish County. This photograph reminds me of the famous last paragraph in "On the Origin of Species", which contains the famous dictum "There is grandeur in this view of life". To refresh your memory, the entire passage runs like this: "It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved". |

|

|

| |

Solitary Daffodil | |

|

|

This solitary daffodil in the field behind my house reminds me of the famous painting of Irises by Vincent van Gogh (right). Irises was the first, and most famous, of 130 paintings van Gogh created in 1889, the year before his death, when he was a voluntary inmate at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Beset by crushing depression and debilitating episodes of agitated confusion, he saw artistic creation, through painting, as his last, best hope to preserve his crumbling sanity. The irises he painted were in a garden on the asylum grounds. Irises, the experts at www.VincentVanGogh.org tell me, was intended as a study in form and colour. Each petal on each flower is shaped exactly, and every one is different from all the others. Much speculation has arisen about the significance of the single white iris among the blue ones. (They were originally purple, but have faded over time.) A common theme is that the white iris represents van Gogh’s own loneliness and isolation. Van Gogh was not a popular man. In February, 1889, residents of Arles circulated a petition to have him removed. I’m not sure. Look at the way the blue irises, especially the clump at the right front, point the eye toward the white one. One can imagine the blue irises aren’t excluding the white iris, but rather turning toward it respectfully, as a congregation attending a white-robed preacher. Maybe the white iris should be seen as exceptional, an exemplar of independence and leadership. If standing apart from the crowd is the theme, the daffodil in my yard has taken it to extremes. There are clumps of daffodils in the gardens nearby, but this rebel is growing all by itself, unweeded and untended, in the semi-wild land beyond the reach of the lawn mower. Not for this one the comforting clump of fellow flowers and their life of weed-free, compost-amended ease. Like van Gogh at St.-Paul-de-Mausole, it has chosen a life of isolation, where it may thrive or perish on its own. There is an air of determination about this solitary plant, defiantly raising its single, bright flower like a clenched fist above the greenery, over-run, but not quite overwhelmed, by competing grass. If I were a van Gogh, I would paint the scene with the garden flowers turning toward the outlier, to welcome it as a prophet who has wandered the wastelands and found a new sense of itself in the world. |

|

|

| |

Two-Trunked Apple I have long been impressed with the capacity of many trees, apple trees in particular, to regrow after a devastating accident. Here is an apple tree, growing among the ruins of a long-abandoned orchard near Antigonish. All the debris in the middle comes from another tree that has fallen on it. You will notice at once that the tree has two trunks. A massive horizontal branch grows out of the left trunk at ground level. The right trunk projects upward about two metres along the recumbent branch, lending the entire tree the shape of the letter 'U'. Both trunks appear equally tall, healthy and robust (“Two households, both alike in dignity” – Shakespeare). We can speculate on the history that led to this peculiar morphology. The recumbent branch is, I believe, the original trunk of the tree. It was split at some time in the past, perhaps by a windstorm, but both halves survived. The remnant of the original tree regrew to become the left trunk. The fallen half, following the gravity-defying imperative of its auxins, extended a new shoot orthogonal to the stem, which in time enlarged to become the right trunk. I wonder if the apples from the two sides of the tree taste different. Perhaps those from the left trunk are a little off, while those from the other trunk taste right. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Waterlogged Sorry, I just threw this one in for the visual pun. |

|

| |

|

The Ocean Gone Viral Consider, for a moment, this assessment of the abundance of viral particles in the world's oceans: There are perhaps 10 million virus particles in every millilitre of seawater, making viruses by far the most abundant biological entities in the sea. By one estimate, there may be 1023 viral infections every second in the sea. For scale, remember that 1023 is also Avagadro's number, describing the number of molecules in a mole of any substance. The mass of carbon in all those virus particles is equivalent to that in 75 million blue whales. Or to put it another way, laid end to end, the viruses in the world's oceans would extend beyond the next 60 galaxies in the universe. The number is literally astronomical. [Source: Archibald, J. 2018. Genomics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK] | |

|

|

|

|

That's Not Mr. Bunny Living out in the country, we are accustomed to seeing wildlife in the yard. Deer, rabbits (really showshoe hares) and porcupines, most often. I was surprised one May morning, however, to discover a half-grown black bear, bearly a year old by the size of it, wandering about our back yard, a few metres from the house. | |

|

|

|

|

The bear spent close to an hour wandering about the yard, discomfitingly close to the house, looking around, eating young grass shoots, and considerately posing for photographs. Our back yard does tend to be a little bear this time of year. | |

|

| |

|

I was fine with having a bear drop by, but I protested when it began to pull up tulips from the garden. Rather than stepping outside and wrestling with it (my idea), my spouse suggested tapping loudly on the window pane to startle the bear into leaving. This tactic did not succeed: |

|

|

| |

|

I can honestly say I have never seen a bear this close before. The claws are impressive. Eventually, after peering in through several windows, the curious bear decided she had seen enough. She wandered off to check out my compost bin, then ambled into the woods. I never expected I would have to clean a bear-paw print off my bedroom window. | |

|

|

Funny Bunny Every year, when spring arrives, snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) gravitate toward my lawn, to take advantage of the abundant dandelions and other greenery there. If you look closely at the photo to the left, you will notice something unusual: this bunny has three ears. More exactly, it has three pinnae, to satisfy any anatomical precisionists who may read this. A rabbit could acquire three ears in at least three ways. It could be a simple developmental deformity, like a deviated nasal septum; it could be a result of a physical trauma, such as an encounter with an unlucky predator that ripped one ear down its length, from which injury the ear subsequently recovered; or it could be a harmless genetic mutation, like Morton’s toe (second toe longer than the first) or being a Toronto Maple Leafs fan. The internet says that rabbits with four ears are not unknown. One can find pictures and videos of them on-line, usually accompanied by a long discussion under the heading “What is this?”. But a four-eared rabbit is comparatively simple to explain. It requires only a doubling of the genetic mechanism that produces ears. Three ears is more challenging, because of the asymmetry, especially in this instance where the third ear appears to be growing exactly in between the other two. At the time this picture was taken, in May, the hares in my yard had started to display active jumping and chasing behaviour, which in the past has been succeeded by baby bunnies dashing about everywhere. I was hoping we might see a whole family of three-eared hares. Unfortunately, the hare in the photo soon disappeared. I can’t confirm whether the three-eared condition breeds true in the F2 generation. |

|

|

|

|

Rat Musqué Dessous La Glace I spent several winters, along with my colleague Randy Lauff, drilling holes through the ice on frozen ponds, in search of invertebrates that remain active in the cold water. I was curious about the possibility that benthic insects such as caddisflies might live on the underside of the ice itself, using it as a kind of inverted substratum. I used a GoProtm camera mounted on an articulated stick so that it aimed at the ice surface from below. The borehole and the stick holding the camera are visible at the bottom of the image. The small black

dots are larval caddisflies, Platycentropus radiatus, crawling on the bottom of the ice. Water

temperature beneath pond ice is ~0.5oC. This is cool biology both literally and figuratively. There is something serenely oblivious in the passage of this hypogean muskrat. Though it swam by almost

beneath me, I was completely unaware of it until I saw the video images. The muskrat, for its part,

either did not notice me or didn’t care. Perhaps it did see the ice hole and the camera protruding into

the water, but since neither of these suggested food or a predator, it paid no attention. It swam away,

intent on its original purpose, undistracted by irrelevant curiosity. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” Socrates claimed. But perhaps muskrats are too busy surviving

the winter to make time for reflection. Or maybe, like cats, they are content to simply be.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Yellow-Eyed Penguin Here is a picture of a (tagged) yellow-eye penguin (Megadyptes antipodes), a bird native to New Zealand and nearby islands. The species is unique (I am told) because it is the only penguin with yellow eyes and yellow feathers on the head. The picture was provided by my well-travelled colleague Dr. Jamie Tam. I include the picture here solely because penguins are very cool birds. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Visiting Bobcat January 2016 was memorable for deep cold and endless snow. Winter is a difficult time for large predators, and one of the main prey items in our area, snowshoe hares, were at the nadir of their more-or-less decadal population cycle. Hunger and bitter weather apparently drove this bobcat (Lynx rufus) to check out the action at my bird feeder, and in the daytime at that. It spent a long time sitting beside a nearby tree watching the birds come and go, and thoughtfully giving me time to take pictures. Eventually it decided that chickadees and blue jays weren’t worth the effort (a tiny bit of meat for a mouthful of feathers) and slipped away back into the woods. |

|

|

|

|

|

Two-Tone Squirrel Black squirrels and grey squirrels, so common in southeastern Canada, are members of the same species (Sciurus carolinensis); the black squirrels are a melanistic phase of the commoner grey squirrels. But any given squirrel is grey or black. This squirrel, however, photographed near Ottawa in spring 2011, is half-grey and half-black, apparently because the spring molt proceeds from nose to tail, and it was changing colour phase with the season. Is this a common occurrence? I have no idea. (Photograph by Richard Taylor) |

|

|

|

|

|

Never Say Die These are the remains of a white ash tree (Fraxinus americana), formerly growing on the bank of Brierly Brook, near Antigonish. At some time in the past it was cut down with a saw (note the flat top at the left end of the trunk). Then bank erosion along this unstable stream washed the stump, roots and all, into the middle of the brook. Half its roots are under water, the other half are in the air. But: It's still alive! A (former) side branch has put out new leaves and is on its way to becoming the new main stem. Here is a tree that simply refuses to give up. |

|

|

|

|

|

Punctuated Maple This is a red maple (Acer rubrum) leaf used in a decomposition experiment in Waughs River, Colchester County. Where did the holes come from? Leaf litter in these experiments is confined in mesh bags that let leaf-feeding insects in, but keep leaf fragments from washing away. The exception is the Giant Stonefly (Pteronarcys sp.), which, being too big to pass even the 1-cm mesh of our litter bags, bit out pieces through the mesh, leaving a neat imprint of the mesh pattern on the leaf. (Photograph by Heather MacDonald) |

|

|

|

Organized Black Flies The picture below left shows a fallen log wedged across Brierly Brook, near Antigonish. Water is flowing over the log, from top to bottom in the photograph. The small dark shapes are larval black flies (Simuliidae) which attach themselves to solid surfaces by a sucker on their posterior end and feed by filtering minute particles from the water. Remarkably, simuliids are territorial, and aggressively defend their location against neighbours directly upstream, who would reduce their food supply. The result of this aggression is larvae arranged in staggered rows to avoid feeding in the lee of another larva. This positioning is apparent in the close-up photograph, below right. Each larva is positioned to the left or right of the one upstream from it, often leading to neat rows of larvae extending at an angle across the log. (see Hart, D. D. 1986. The adaptive significance of territoriality in filter-feeding larval blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae). Oikos 46: 88-92) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Never Say Die (Part 2) It is not unusual to see trees in a mature forest with trunks that are bent at a right angle or even an S-curve. These shapes arise from another tree falling on the victim when it was young, bending it over without breaking it. The bent tree then regrows upward, retaining the bend in its trunk long after the fallen tree has rotted away. This yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), growing in a birch-maple forest in the hills above the Wentworth Valley, Colchester County, has taken this persistence to an extreme. The trunk grows up for 2 m, bends 90° left, executes a hairpin turn, and then swings upward again. The trajectory of the growing trunk covers 360°. Yet the canopy of this tree is as leafy and healthy as any in the forest around it. Another tree that simply refuses to give up. (Photograph by Ian Bryson) |

|

|

The Deer Hunter Here is an excerpt from a brief article by Tim Heffernan in The Atlantic, November 2012: "Here are some curious facts. One: more white-tailed deer live in the United States today than at any other time in history. Two: fewer hunters are going after them than did even 20 years ago. And yet, three: deer hunting now rivals military combat in its technological sophistication. [ . . .] The average American hunter now spends nearly $2500 a year on the sport, despite the fact that finding a deer to kill has literally never been easier." (The Atlantic website)

|

|

|

|

|

|

A great blue heron (Ardea herodias) fishing in a wetland stream behind Antigonish Mall, August 2013. Great blue herons are very cool birds. |

Last modified: 11 April 2023

These swallowtail butterflies (Papilio glaucus) photographed through a forest of sedges along South River, are engaged in an activity known as puddling. Adult butterflies live on a diet of flower nectar, which provides all the energy they need but none of the minerals. To remedy this imbalance, they sometimes gather on wet mud where they can draw up interstitial water that is rich in minerals, especially sodium, as well as organic compounds such as amino acids. Puddling is common, according to various internet sources, among members of the swallowtail family (Papilionidae), as well as sulfurs and whites (Pieridae).

These swallowtail butterflies (Papilio glaucus) photographed through a forest of sedges along South River, are engaged in an activity known as puddling. Adult butterflies live on a diet of flower nectar, which provides all the energy they need but none of the minerals. To remedy this imbalance, they sometimes gather on wet mud where they can draw up interstitial water that is rich in minerals, especially sodium, as well as organic compounds such as amino acids. Puddling is common, according to various internet sources, among members of the swallowtail family (Papilionidae), as well as sulfurs and whites (Pieridae). The previous owners of the house where I live now kept horses for their kids.

They built a barn and a paddock behind it. This would have been in the 1980s, about the time that

I was finishing my doctorate at the University of Calgary. The horse paddock is long gone, but the

corner posts remain, their tenure unnaturally preserved by heavy applications of creosote,

a petroleum derivative that inhibits growth of fungi.

The previous owners of the house where I live now kept horses for their kids.

They built a barn and a paddock behind it. This would have been in the 1980s, about the time that

I was finishing my doctorate at the University of Calgary. The horse paddock is long gone, but the

corner posts remain, their tenure unnaturally preserved by heavy applications of creosote,

a petroleum derivative that inhibits growth of fungi.

This picture, taken in February on a pond near my house, shows the unexpected passage of a muskrat

(Ondatra zibethicus) swimming by less than a metre from where I was standing. He could have passed

directly beneath my feet without me knowing it. Clearly, animals other than benthic insects are very active

beneath the ice in frozen ponds.

This picture, taken in February on a pond near my house, shows the unexpected passage of a muskrat

(Ondatra zibethicus) swimming by less than a metre from where I was standing. He could have passed

directly beneath my feet without me knowing it. Clearly, animals other than benthic insects are very active

beneath the ice in frozen ponds.