Bantjes, Rod, “Field_Def.html,” in Eigg Mountain Settlement History, last modified, 14 August 2015 (http://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/gis/txt/eigg/introduction.html).

What is a Field? (Eigg Mountain Settlement History)

While painstakingly trying to discern the transitions between one type of vegetation and another and so determine the boundaries of fields, I have thought about the question of what a field is. You might think of it as an area where people have worked to promote the dominance of a set of favoured plants over all others. These plants are selected because humans love to eat them or because they use them to feed the animals that people feed upon. Some field plants like hemp or indigo serve industrial purposes. (Trees though, whether for food or industrial purposes, are never, even when planted, thought to constitute fields.)

|

Figure 1 – Prairie Fields near Regina Saskatchewan. |

| Even here plants in wet areas do not fully co-operate with the rectangular logic. Image taken from Google Earth, Copyright 2015 Google, reproduced here under U.S. copyright law governing “fair use.” |

We have become accustomed to the idea of fields with boundaries that are heavily “policed.” We think of them as following property lines exactly, and, in much of the country, particularly in Western Canada, those lines are dead-straight and square (see Figure 1). Within the lines, the select plants are encouraged and invaders are eradicated by the use powerful machine and chemical tools. If the select plants are hardy enough to spill over the boundaries (in the way that the Jerusalem Artichokes in my garden are doing at present) does that extend the field boundaries? If the surrounding vegetation (or weeds) retakes an area, then is that area no longer a field? How weedy does a field have to be in order to become no longer a field?[1] In other words, how much “say” do plants themselves have in defining the boundaries of fields?

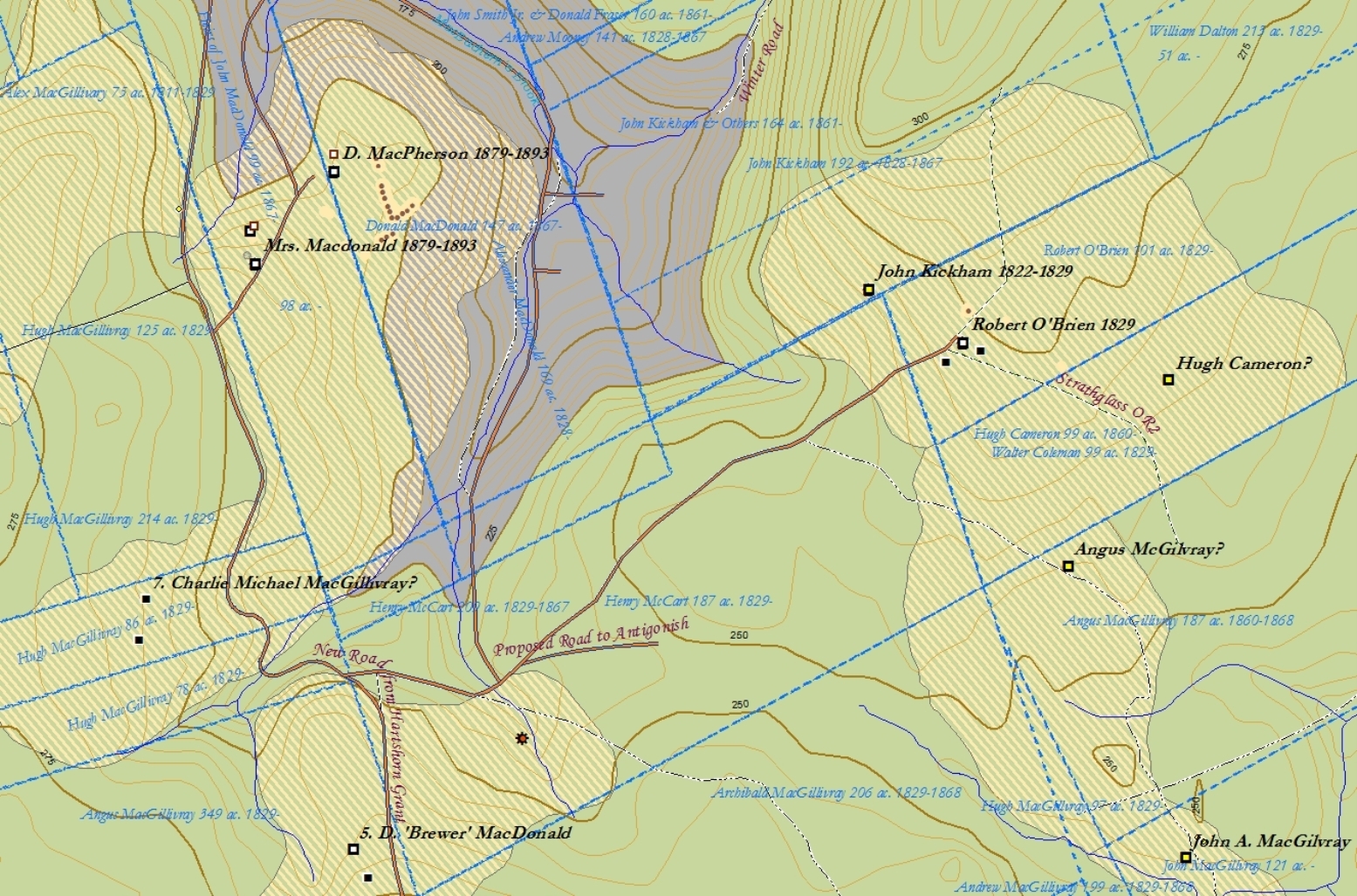

Between a hundred and two hundred years ago on Eigg Mountain, it was as though the farmers forged negotiated settlements between the lines of property, the peculiarities of the land and the preferences of the various plants involved. They only very loosely followed property lines. In some instances this was because property lines were not defined very well by surveyors. Mostly, they seem to have extended fields where their crops throve or their foraging animals found feed, and let the forest, or wetlands remain or creep back in areas where select plants had a tough time taking hold. The result was fields with organic, irregular shapes that probably changed over time. In following the needs and propensities of plants rather than the lines of surveyors, farmers annexed bits and pieces of adjacent properties (see Figure 2). The ethic probably was not greed or expansionism but something rather more like sharing for survival. So long as no-one else was using it, or was likely to use it, adjacent land amenable to cultivation should go to those best able to benefit from it.[2]

|

Figure 2 – Field and Property Boundaries. |

| Fields are indicated by diagonal yellow stripes; property in dotted blue lines. |

On properties where family members farmed together, while there are different dwellings, there often appears to be almost no distinction made between fields. This makes me wonder whether they were tilled, planted and harvested in common.

To return to the question of drawing the boundaries between field and not field, if it is, as I have suggested, an unstable negotiation between humans and plants, where the autonomous action of the plants is a force in the resulting line, who decides exactly where human preference and plant preference prevails? Even the lines that the farmer intended are no longer decisive if plants have a say. In other words is there such a thing as an objective field boundary? This might seem like a purely philosophical question (and there is nothing wrong with that) but to me, trying as accurately as possible to draw the lines that bounded old fields on the map, it became a question of practical application.