5.1 History of Eel Fishing in Nova Scotia and Antigonish

Eel fishing in Nova Scotia has a history from the first people (Mi'Kmaq) to the present day population of peoples. The very early fisheries, 3000 years ago, consisted of stone weirs constructed on rivers, eelpots made of ash splints to spears for winter and summer fishing (Gordon 1993).

Mi'Kmaq fishing was done primarily to acquire food in preparation for the long seasons endured by the people. In the early days of the Mi'Kmaq food was gathered to feed the people and to be shared by all. The concept of selling food was not practiced in a direct sense, for food was a gift from the Creator and available to all and distributed for the community. Food was shared in a way like that of the wolves, who fed in packs on large kills, each member having their place in the structured order.

With the early contact of western culture the Mi'Kmaq could not understand the concept of selling food like cod and seeing it caught in such large quantities then shipped away. This led to concerns about the future of the people and their food supply.

Articles for hunting, fishing and shelter were traded and the best of hides and articles were saved and used as gifts. This demonstrated one's ability of hunting and gathering but most of all, their ability to share and contribute to the well being of the community. Food, seeds and medicinal plants were traded or exchanged during long trade missions to different tribal territories. This sort of trading led to the small cultivation of food and medicinal plants that were not growing in the general area. Eel was a food supplement that was available year round, along the coastal areas and the inland river and lake systems.

Eel fishing in Nova Scotia in the late 1800s to mid 1900s was conducted on a small scale. The St. George's Bay area, located off the coast of Antigonish, was one of the most productive eel fishing areas in Nova Scotia. Mi'Kmaq from the different communities in Cape Breton and the Truro - Shubenacadie area came to fish, using the rail service that stretched from Truro to Sydney. Many would stay with local Mi'Kmaq families that camped around the area. Local French - Acadian communities also fished for eels in these waters.

Eels were not sold in large quantities from this area but instead were peddled through the communities. This work supplemented whatever small incomes the people had. Large portions of the eels caught were for personal use, primarily as food. The best eeling areas in St. George's Bay were at Lakevale, Harver Boucher, Pomquet and Antigonish Harbour (Eales 1966). See figure 8 to locate these fishing areas in St. Georges Bay.

The eel fishery in the Antigonish area remained a small scale fishery done through peddling into the 1960s.At that time however, studies were being done around the province to assess where the potential for commercial fishing existed and the St. George's Bay area was documented as a potential area (Eales 1966). Figure 9 illustrates the situation of the eel fishery in the Maritimes, Nova Scotia, and St. Georges Bay in the 1960s.

Figure

8. The best eeling areas in St. George’s Bay were at Lakevale,

Harver Boucher, Pomquet and Antigonish Harbour

Source: Davis

1999.

Figure 9. This map illustrates the situation of the eel fishery in the Maritime Provinces in the 1960s. St. Georges Bay area, circled in red, is documented as having an unknown potential for commercial fisheries. The eel fishery at that time in the Bay was still a small-scale fishery conducted by peddlers.

5.2 Gear and Methods

Eels were fished in six different ways in Nova Scotia using baited traps, unbaited traps, weirs, spears, hooks, and nets.

Baited traps varied in size and shape depending on the material they were made of.Some were woven basket traps while others were modified lobster traps. Eels were attracted by bait placed in the trap and entered through a funnel narrowing inward into a chamber where the eel was enclosed.

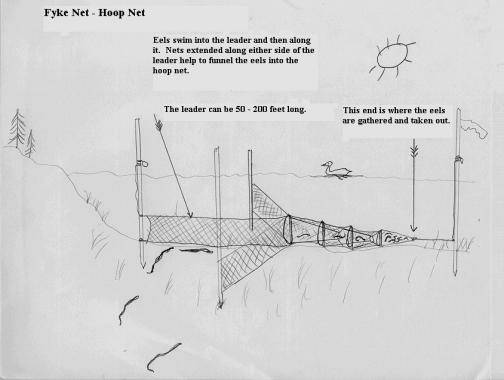

Unbaited traps were made of fyke and hoop nets. These traps have long wings that steer eels into a funnel of hoops that narrow and trap the eels. The wings may vary in length depending on the bottom type and where they were set. These nets were often placed along estuaries in the eelgrass. Figure 10 illustrates the working of a fyke net - hoop net system to catch eels.

Weirs were used in the river system. These were funnel or v-like structures that trapped eels moving down river during the fall migration of the silver eel. They were made of stone and other materials like trees and branches for the long wings. Stone weirs were commonly made in the river and the wood type in the estuaries.

Figure

10. This picture illustrates the working of a fyke net - hoop

net system to catch eels.

Credit: K. Prosper 2001.

Efficiency on the more successful weirs would produce four and a half pounds per person an hour. The time it took to tend a weir was a few hours a day depending on the number people working. Estuary weirs average a catch per day of 100 lbs. and 25,000 lbs. per season by one fisher (Eales1966).

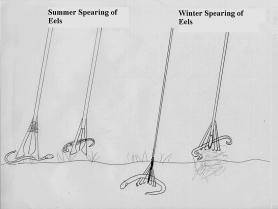

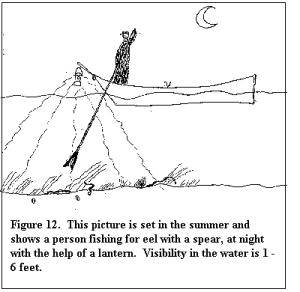

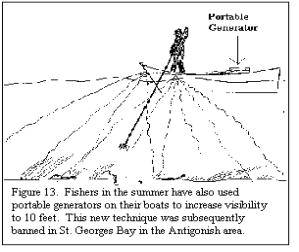

Fishing for eel with a spear is the most common method and is done year round.Spears used in the summer and winter have different spearheads, shown in figure 11, but are the same length from 15 - 20 feet. In the summer eels were speared from boats at night with the aid of lanterns (figure 12) and at times generators which enabled greater visibility into the water (figure 13). Eel fishing with a spear would continue through the fall (figure 13) and into the winter out on the ice through holes (figure 14).

Spear fishing for eel was very common in the Antigonish area and the Maritimes. Approximately one third of the eel caught, in the Maritimes in 1962 were taken by spears. The efficiency of this method varies greatly depending on the skill of the fishermen. A good fisherman could catch up to 40 to 50 eels weighing 2 pounds each in 1 to 2 hours (Eales 1966).

Figure

11. Spears used in the summer and winter have different spearheads

but are the same length from 15 - 20 feet.

Credit: K.

Prosper 2001.

Another method of catching eels was with long trawls that carried up to 500 hooks and were baited with herring and live minnow. The trawls were set in 4 to 6 feet of water at night when the eels were most active. Trawls were hauled in the morning and the catches were between 300 to 400 lbs. a day with a good year yielding 15,000 lbs.

5.3 Commercial Development of the Eel Fishery

In the 1960's the export of eels in the Maritime region was to markets in the U.S.A., Canada and Europe. In Nova Scotia, from the early 1900's to the 1960's, the total catch fluctuated fairly regularly between 35 to 75 tons. The value of catch ranged from $5,000 to $20,000 with a peak in 1955 of $30,000, see figure 16. For the Gulf of St. Lawrence region, there was an increase in landings in the 1960's corresponding to increased fishing effort, and the introduction of fyke nets. Most of the landings were in the northwestern Cape Breton district. These catches peaked and fell quickly in the 1970's and the reduced catches have developed into a long-term decline. General decrease in catch is thought to reflect widespread population decline.

In the 1970's new licenses were available to bonafide fisherman and non-commercial fisherman using eel pots. Seasons were from Aug. 15 to Oct. 30. The spear fishery continued year round without any season or licensed regulations. Mi'Kmaq and surrounding communities continued to fish for food and peddled the eels.

In the late 1980's, the price of eel continued to rise and many more people started to fish and sell eels. Fishing occurred year around, except in spring when the ice was thawing. On some given days there would be over a hundred people on the ice of Antigonish Harbour, fishing eels using spears and selling to buyers who came to the ice to buy. The price of eels varied from 2.50 to 3.50 per pound. This was a good price and the gear, a spear, would not cost more than fifty dollars.

In the mid-1980s, the commercial eel fishery in Prince Edward Island suffered a fall in catch.In 1986 PEI landed 225 tons of American eel which would eventually fall to 55 tons in 1999. The eel fishery in New Brunswick began to mirror the fall in PEI in 1990. The New Brunswick catch fell from a peak of 330 tons in 1989 to only 30 tons in 1999. During the 1980's the eel fishery in Nova Scotia remained stable and landings recorded were consistent with previous years. As the fisheries in NB and PEI declined steeply, recorded landings in Nova Scotia, in the early 1990's began to increase rapidly, see figure 17.

With the collapse of the eel fishery elsewhere, and the mobile nature of spearing, fishers from the other Maritime Provinces came to Nova Scotia to fish.In the experience of local fishers from the St. Georges Bay area, fishers came from the PEI to fish eels around Nova Scotia bringing new ideas like the generator and flood lights. The easy mobility of the eel fishery enabled fishers to go to any estuary along the coast and many good fishers could land up to a thousand pounds on a good night of fishing.

Local fishers became concerned for the security of the food fishery when they witnessed the large catches and intense methods of fishing being used by the out of province fishers and took their concerns to DFO.Some of the efforts of the concerned food fishers were met with the banning of the electronic light fishery and reintroduction of the gas lantern. In addition, the reports and complaints to DFO may have led to the freeze in of new licenses in 1991 and the implementation of requirement of a commercial license to fish eels with spears.Perhaps the greatsest accomplishment of the food fisher’s lobbying was the partial closure of Pomquet estuary to commercial fishermen and its reservation for the local food fishery. However, today there are very few eels caught in the Pomquet estuary and although the Antigonish Harbour was a main food fishing estuary for the Mi'Kmaq and surrounding communities the commercial eel fishery continued there.

To further express their concern the local Mi'Kmaq community wrote to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and requested the closure of the commercial eel fishery. Meetings were held with the fishers and the community members surrounding the estuaries being fished. A dramatic increase in the landings of eels in the St. Georges Bay area in 1993 were recorded, especially in Antigonish Harbour and Pomquet estuary. Following 1993 a steady drop in the landings occurred in the St. Georges Bay area to 1998 when very small landings were then recorded (Davis 1999). This trend of high catches in the years 1992 - 1995 were experienced throughout Nova Scotia with peak landings of 165 tons in 1993. The peak of 1993 was short lived and landings in Nova Scotia began to decline, from 165 tons to a mere 10 tons in 1999. Shooting in the opposite direction from landings was the dollar value of the eel. The value of catch in Nova Scotia rose from $600,000 in 1994 to $2,150,000 in 1997 and subsequently fell to $100,000 in 1999, see figure 17.

The introduction of an experimental elver fishery in 1994 in the Scotia-Fundy area was also a concern for all involved in the food fishery. The development of an elver fishery will have a large affect on the future of the eel population as the eels will be fished before they have a chance to go upstream to mature.The elver fishery went ahead in spite of the opposition from Mi'Kmaq communities and continues today. The development of this fishery fits well with the recent increased demand and price for juvenile eels (glass eels and elvers) for the oversea aquaculture industry (primarily Asia). Increases in directed fishing effort for this life stage in some locations of Eastern Canada and Maine have been documented (Meister and Flagg 1997).

Paulin (1997), summarizes the commercial American eel fishery to that date:

1970's:

Season from August 15 to October 30

Licensing available only to bonifide fishers, except in Margaree

Licensing of non-commercial fishers using pots

Spear fishers required no license and no seasonal restrictions

1991:

Freeze on all new licenses for all gear types

1993:

Implementation of licensing commercial spear fishery

1995-96:

Season from April 1-30, and August 16 – November 15 for nets, pots

Closure of Pomquet Harbour

Minimum size of 46cm introduced

Voluntary bag

limit of 10 suggested for recreational fishers.

1997:

License required for spear fishery, restriction on intensity of light

used, season from January 15 to June 30, minimum length of 50cm

Season runs

from September 1 to October 30 for other eel fisheries.

DFO fishery policy decisions are based on scientific data on species and stock assessments isolated from its users, the people who depend upon it. The role of science in the Mi'Kmaq world-view plays a very different role in that it is directly related to the ecosystem which the people are a part of. Understanding the nature of the ecosystem and everything in it was vital for the continued good health of the people.In the past whether the people decided to stay in a given area for another winter would be determined by the knowledge of the elders, hunters and fishers reporting the success rate and the spiritual guidance of the shaman. This process ensured the survival of the people and the future sustainability of the ecosystem that supplied the necessaries of a good life.If the ecosystem were to be unbalanced then the people would suffer re-adjusting the balance, re-establishing sustainability.

Today this is not the same, ecosystems have to supply more than a good life. They must supply lives of luxury and an imbalance in levels of living throughout the world. Sharing is not so important today and people continue to suffer while many have much more than they need. Gathering food today is much different and is done in a different way. instead of gathering food from our waters, woods and land for ourselves, we are gathering it for consumption on the other side of the world. It is based on an economy and this drives the kind of food grown, gathered and traded on a worldwide basis. Decisions are much more complex and are influenced by the world leaders and corporate giants that turn the economic wheels of our nations.

Figure 16.Time Series of Maritime Eel Landings and Value of Catch for 1920 - 1962. Data Source: Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries, Economica Branch.1966.

Figure 17.Times Series of Maritime Eel Landings and Value of Catch for 1972 – 1999. Data Source: Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Statistics Branch.

5.4 Mi'Kmaq Fishing Rights

The concern over the existence of a food fishery is closely linked to the Mi'Kmaq world-view and tradition. Food gathering and consuming is not merely a means to remain alive but is a part of one’s life. The protection of the right to gather food is often excluded or not considered in the making of regulations and establishing of commercial markets. In 1990 Ronald Sparrow from the Musqueam Band in British Columbia won a court case whereby the right of Aboriginal people to fish for food was recognised. This ruling also stated that if the Fisheries Act and regulations were inconsistent with the constitutional guarantee of the aboriginal right to fish, then the aboriginal right to fish would prevail.

On the issue of conservation, the Supreme Court states:

"The constitutional nature of the Musqueam food fishing rights means that any allocation of priorities after valid conservation measures have been implemented must give top priority to Indian food fishing….If , in a given year, conservation needs required a reduction in the number of fish to be caught such that the number equaled the number required for food by the Indians, then all the fish available after conservation would go to the according to the constitutional nature of their fishing right. If, more realistically, there were still more fish after the Indian food requirements were met, then the brunt of conservation would be borne by the practices of the sport fishing and commercial fishing. "

(www.lexum.umontral.ca/csc-scc/en/pub/1990/vol1/html/1990scr1_1075.html)

Mi'Kmaq concern for the food fishery in light of DFO management of the fisheries raises a number of questions.

Have the policy makers changed or adjusted fisheries management and regulations to assure the protection of the food requirements of the First Nation People, as they have been legislated to do by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Sparrow, 1990 and other court rulings?

When should a commercial fishery be stopped to sustain food requirements?

How can management and First Nations work together in preventing a collapse of a food resource?

In

August 24 of 1993, Donald Marshall Jr. was charged for fishing and selling

eels without a commercial D.F.O. license. In 1999 Donald Marshall Jr.

won his court case affirming the right of Mi'Kmaq to fish commercially

(www.lexum.umontreal.ca/csc-scc/en/pub/1999/vol3/html/1999scr3_0533.html)

5.5 Fisheries Science

Standard fisheries management approaches have not provided a clear understanding of status of the American eel.Catches in North America are declining (Locke et al, 1995 and Haro et al. 2000).The area with the most successful fishery, in the St. Lawrence River (Anonymous 1984) has witnessed a decline of 98% of juvenile eels returning from the ocean in the period from 1985 to 1992. (Castonguay et al 1994).This has been attributed to a combination of four factors: change in habitats, overfishing, chemical contamination, and a change in ocean climate (Castonguay et al 1994).

Questions and Knowledge Gaps in Fisheries Science of the American Eel

Fishing Mortality:

Absence of basic population dynamics data for American eels has not enabled an evaluation of the effects of potentially high exploitation rates on regional stocks and the population.

Estimates of exploitation rates for numerous regional stocks into one exploitation rate for the single panmictic population does not exist for the American eel (Haro et al. 2000).

High fishing mortality on glass eels and pigmented elvers may contribute to reduced recruitment into freshwater nursery areas.

Fisheries targeting yellow and silver phase eels may impact regional stocks and reduce the contribution of some watersheds to the panmictic spawning population (American Eel Plan Development Team2000).

Oceanic Variation:

The oceanic phase of the species life history, including migration of adults to the spawning area, spawning behavior, larval drift, and recruitment of postlarvae and glass eels to coastal areas are poorly understood.

Changes in the strength and direction of ocean currents affect the distribution and recruitment of larval and postlarval eels into coastal habitat (Jessop 1998).

Contaminants:

Because the eels live on the bottom of the estuaries, rivers and lakes and spend the winter buried in the sediments - they are susceptible to poisoning and bioaccumulation of contaminants (Haro et al, 2000). There have been documented studies of accumulation on PCBs, lead and impairment caused by pesticides in the water systems (Haro et al, 2000).

When spearing eels, the bottom sediments get stirred up and re-released into the water column - what effects might that have on the eels?

Disease:

Within the last several years, an exotic Asian swim bladder nematode (Anguillicola crassus) has been identified in American eels. The pathogenicity of A. crassus in American eels is unknown. A wide spread infestation could have dramatic effects at the population level.

Riverine Passage:

The affect of dams and other river obstructions on the eel population is not known. Because the sex of the eel is determined by environmental conditions, high concentrations of eels below river obstructions could possibly result in more males than females (Haro et al, 2000).

High concentrations of eels below obstructions could also cause increased mortality because of increased predation, competition for food, spread of disease

No studies have been done on downstream migration of eels and their behaviour around dams (Haro et al, 2000). Death and injury of eels as a result of dams and turbines has been documented (Berg, 1986; Desrochers, 1994; Monten, 1985, Palmer et al, 1997; in Haro et al, 2000)

What happens to the eels who are prevented from migrating upstream by dams and other obstructions is unknown and undocumented (Haro et al, 2000).

Habitat Degradation:

Fragmentation and/or alteration of freshwater habitats affect the quality and suitability of habitats for eels. Changing land use around the rivers, ponds, lakes affect the aquatic habitat.

It is not known what reproductive contribution eels from a particular habitat may have on the eel population as a whole (Casselman et al, 1997b in Haro et al, 2000). As a result it is unknown what kind of impact a change in the eel's habitat in a particular system may have on the eel population as a whole.