Topic #7 – Strings & Objects¶

The thing about strings¶

Activity

How is a string different from the other data types we’ve seen (int, float, numpy.float32, bool)?

I can print individual characters of a string, by indexing the string:

>>> a='My little string' >>> print(a[0]) M

>>> print(a[1]) y

A string is just a… string… of characters

In a compound object, indexing allows us to pick out individual components.

- Note that in Python, the first index is

0, not1! Whether to start at zero or one is an arbitrary decision made by programming language designers.

Python inherited the 0-based convention from C (this actually makes sense if/when you learn about memory pointers)

MATLAB inherited 1-based indexing from Fortran

- Note that in Python, the first index is

Activity

Write a single line command to print the first 4 characters of some string a.

How about the 2nd to 7th characters?

How about the last three characters?

Hint: what does a negative index do?

Bonus if you’re reading ahead: what does

print(a[0:4])do?This is called slicing the string.

More loops¶

- I can get the length of string like this:

>>> len(a) 15

Let’s apply that…

Activity

Write a function

vert_printthat takes a string as an argument and then uses awhileloop to print each character on its own line. (See sample output below)

>>> vert_print(a)

M

y

_

l

i

t

t

l

e

_

s

t

r

i

n

g

The

whileloop certainly worked OK there, but it was a bit awkward.whileloops are meant to continue until some logical condition is met.Maybe there is another kind of loop that says “Do the indented code block once for each item in a compound object” rather than “Do the code block until an arbitrary condition is met”.

Such a thing exists: the

forloop:for char in a: print(char)

for each character in the string

a, we run the indented code block.You don’t have to use the

forloop. Awhileloop can do exactly the same thing.The

forloop is just cleaner here (and less typing!).But there is nothing wrong with the

while! There are just a lot of ways to solve a problem.- You can actually prove that there are a (countably) infinite number of programs to do any given task.

Some are just more efficient, and easier to read, than others.

Mutability¶

So… if we can access an individual character in a string with an index…

… you might be feeling tempted to try to set an individual character with an index, too.

- Let’s try::

>>> a[7]='X' Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

Variables of some types (like

int) are mutable… that is: they can be changed.Based on the above… do you think strings are mutable?

- You can’t change a string. You have to make a new one based on the old one.

>>> new_a = a[:7] + 'X' + a[8:] >>> print(new_a) My littXe string

in¶

Activity

Write a function char_is_in(char,string) that returns True if the character char appears in the string string.

HINT: what does the

inoperator do in Python?

You can do the above exercise the hard way, with loops, or you can look up

in.

Tricky Activity

What’s wrong with this?:

def char_is_in(char, string):

count = 0

while count < len(string):

if string[count] == char:

return True

else:

return False

count = count + 1

Try: char_is_in(‘t’, ‘test’)

Try: char_is_in(‘z’, ‘test’)

Try: char_is_in(‘e’, ‘test’)

Activity

Write a function where_is(char,string) that returns the index of the first occurrence of char in string.

String Trivia¶

''or""will work for the quotes needed for stringsBut you can put

''inside""s

>>> a = "Hello, 'world'" >>> print(a) Hello, 'world'

- We can concatenate strings

>>> a = 'FuN' + ' ' + 'tImEs' >>> print(a) FuN tImEs

- We can make a string repeat

>>> a = 'FuN' * 3 >>> print(a) FuNFuNFuN

- We can convert an

intto astr >>> print(type(1)) <class 'int'>

>>> print(type(str(1))) <class 'str'>

- We can convert an

- The string

''is a string, but it’s empty This is a weirdly important detail actually

>>> a = '' >>> print(len(a)) 0

>>> print(type(a)) <class 'str'>

- The string

- We have some special characters that we have no buttons for.

‘\n’

‘\t’

‘\\’

There are a bunch

>>> a = 'hello\nWorld\tFUN\\!' >>> print(a) hello World FUN\! # A weird string

- ASCII Table

Every character is a number

>>> wut = ord('a') # get the num of 'a' >>> print(wut) 97

>>> wut = chr(65) # convert num to char >>> print(wut) A

Formatting output¶

%.2f (percent dot two eff)

f is for float

Right side of . is for decimal places

>>> a = 1.235 >>> print('Format to 2 decimal places: %.2f' %a) # it will round too! Format to 2 decimal places: 1.24

>>> b = 4.39999 >>> print('a: %.2f b: %.4f' %(a, b)) # need parentheses if more than one value to be inserted a: 1.24 b: 4.4000

Left side of . is for specifying total string length

>>> a = 1.311 >>> print('3 of the 5 chars: %5.1f' %(a)) 3 of the 5 chars: 1.3 # len('1.3') = 3

>>> print('4 of the 5 chars: %5.2f' %(a)) 4 of the 5 chars: 1.31

>>> print('5 of the 5 chars: %5.3f' %(a)) 5 of the 5 chars: 1.311

Left justify

>>> a = 1.311 >>> print('%-10.2f neato' % a) 1.31 neato

>>> print("%-10s%10.2f" %('Total:', a)) Total: 1.31

- Many old programming languages do it this way

And there are a billion other options too

- There are new ways to format your strings in Python though

- .format()

Probably the best way to do it in Python these days

f-strings

Check them out if you care

Objects¶

Warning

Some of the following is not actually true for Python, but will be the case for many of the commonly used programming languages.

Also, we will be going into more detail on Objects later in the class.

- We have seen primitive types

Int

Float

Booleans

- There are other types:

Strings (actually kinda’ a primitive type in Python, but let’s ignore this …)

Numpy things

These are objects!

We can even make our own objects

These objects act a little differently inside the computer

Methods¶

- We’ve seen built in functions

print('this is a function')

- We’ve written our own functions

char_is_in('a','bleh')

Activity

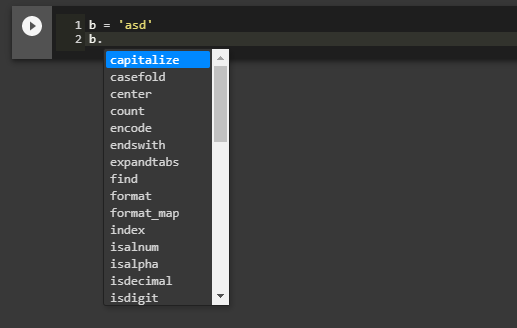

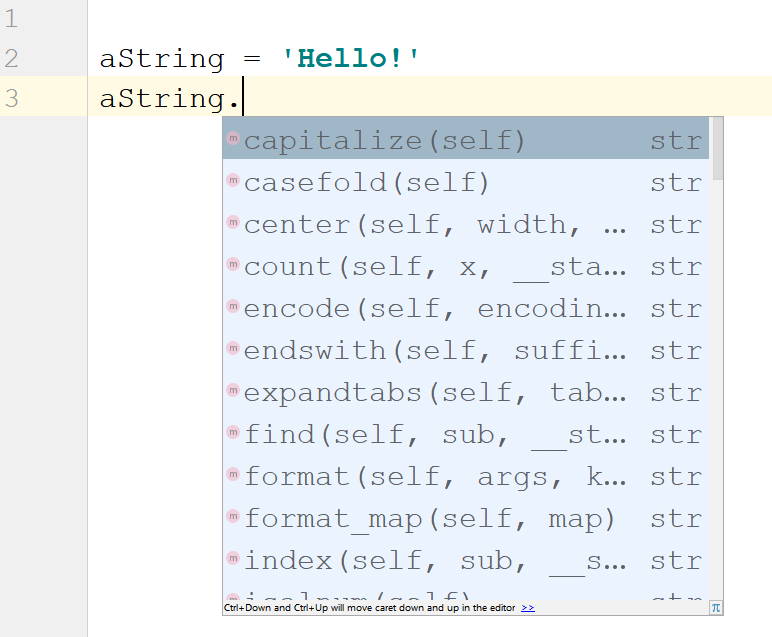

- In Colab:

Make a string

Assign it to a variable (if using Colab, hit run too)

Type the name of the variable

Press dot (period)

Wait… (or space or press ctrl-space (depends on IDE))

Activity

Try writing

a_string.upper()and printing it out.Try some other methods

Methods are very very similar to functions

But we’re telling a specific object to do something

- Long story short:

Sometimes we do things with functions

Sometimes we do things with methods

BUT WAIT…¶

Why do we have to do it like this

a_string.upper()As opposed to like this:

upper(a_string)

Answer¶

Because…

upper(a_string)is not actually definedunless we define it ourselves

These methods were written by someone, and they wrote them to work a certain way

Not necessarily the best way, or a way you like

There’s also a good bookkeeping argument too

Put all the string methods with the strings

How are you supposed to keep track of what’s what?¶

Don’t worry, you’ll get it with practice

Do note though, the key is practice

Heavy lifting with strings¶

- If the program you are writing needs to do a lot of string manipulation, you probably want to

>>> import string