|

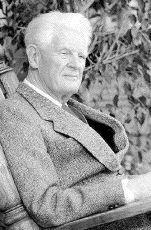

Maple Leaf flag creator George Stanley dies

He was a teacher, a historian and former

lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick

Saturday, September 14, 2002

He was an eminent Canadian historian who -- through mountainous scholarly writings and with a famous flash of inspiration in 1964 -- very much changed the course of the country's history. George Stanley, a former lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick and creator of the Maple Leaf flag, died Friday at 95 after living a life of quintessential Canadianness. A Rhodes Scholar who would star on Oxford's hockey team while crafting the definitive history of Western Canada, Stanley was a Calgary-born Maritimer who helped soothe relations between French and English Canada by rewriting the story of Louis Riel and then by designing Canada's supreme unifying symbol. Born in Calgary in 1907, he had a 33-year teaching career at the University of British Columbia, Royal Military College, and Mount Allison University in Sackville. Stanley also served in the Second World War, retiring in 1946 as the director of the army's historical section. His books included The Birth of Western Canada, which the Canadian Encyclopedia describes as "combining his passion for the West with an appreciation of the importance of military factors." In 1963, he published a biography of Louis Riel. Other works included Canada's Soldiers (1954), and New France: The Last Phase (1968.) He also played a key role in documenting the Canadian experience of the Second World War, working for years with battlefield war artists and extracting painful details of the Dieppe disaster from returning soldiers. As a history professor at the Royal Military College and other universities across the country, Stanley nurtured new generations of scholars, including such prominent Canadian historians as Desmond Morton. "Teaching was his greatest passion," said his wife of 56 years, Ruth. "He was born to it." Remarkably, even as her husband was in the throes of his final illness last week, Mrs. Stanley was sorting through his papers and unearthed a precious, long-lost artifact highlighting his pivotal role at a critical moment in Canada's history. "I'm embarrassed to say it's been here all along," she chuckled. "I couldn't believe it when I found it." From a folder of yellowed documents, she had retrieved a small postcard sent from the House of Commons moments after MPs finally approved the new flag, following months of wrenching debate and a marathon session of the House. "It reads like this," Mrs. Stanley said over the phone. "Tuesday, Dec. 15, 1964, 2 a.m. House of Commons, Canada. Dean George Stanley, RMC. Dear George, your proposed flag has just now been approved by the Commons 163-78. Congratulations. I believe it is an excellent flag that will serve Canada well. John Matheson (Leeds.)" Earlier this year, the Ottawa Citizen revealed that the National Archives had discovered a March 1964 letter from Stanley to Matheson -- the Pearson government's point man on the adoption of a new Canadian flag -- which carried the first-ever illustration of the Maple Leaf design. At the time, Canadians were in the midst of an acrimonious debate over then prime minister Lester B. Pearson's plan to replace the Red Ensign. In his letter, Stanley had explained the need for the new design to draw from the traditions of both French and English Canada so it could serve as a "unifying symbol." And he offered a tiny drawing in red ink that was the first illustration of what would become the country's flag. "The single leaf," he wrote, "has the virtue of simplicity; it emphasizes the distinctive Canadian symbol; and suggests the idea of loyalty to a single country." During his tenure as lieutenant-governor in New Brunswick from 1982 to 1987, Stanley met with most members of the Royal Family and the Pope and presided over the province's bicentennial celebrations. Over the years, his connection to the flag has brought endless accolades and occasional threats. "I was told I had done a great deal of harm to the country," Stanley once said. "I was accused of being a traitor. I even received a letter from a man who said he was going to assassinate me because I assassinated the flag." Among the 18 books and scores of other scholarly publications Stanley produced is a history of Canada's flags. Predictably, it contains only a passing mention of his own role in the adoption of the Maple Leaf design, and is focused on exploring the changing attitudes and traditions around the country's symbol. "A flag," he once wrote, "speaks for the people of a nation or community. It expresses their rejoicing when it is raised on holidays or special occasions. It expresses their sorrow when it flies at half-mast. It honours those who have given their services to the state when it is draped over their coffins. It silently calls all men and women to the service of the land in which they live. It inspires self-sacrifice, loyalty and devotion." The words drive home the significance of his own legacy in Canadian history. Along with his wife, Ruth, Stanley is survived by two grandchildren and three daughters -- Della, Marietta and Laurie -- all of whom are teachers. "They were born to it, too," says Mrs. Stanley. Copyright © 2002 by

The Ottawa Citizen. All rights

reserved. Reprinted with permission. |

|||||||||