Rod Bantjes, “Brunelleschi_Device.html,” last modified, 23 June, 2024 (https://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/).

Brunelleschi Device: The Deceptive "Proof" of Linear Perspective

|

Figure 1 – Brunelleschi Device |

| The device holds an image of an atrium flipped left to right. The viewer stands on the opposite side looking through the peephole in the centre partly at the actual atrium and partly at a mirror image of the photograph of the atrium. |

I knew something had gone terribly wrong when I looked at my first snapshot of the Prairie landscape that I loved. The vast surround of infinite space that I experienced had vanished and been replaced by an impoverished facsimile that had narrowed, shrunken, flattened and deadened the original that it was supposed to represent. I thought I was a bad photographer or that I needed a bigger camera. The problem was in part the reduction of experienced reality to a flat surface in accordance to the geometric logic of linear perspective (depending on the lens, cameras and camera obscuras with pinholes instead of lenses render the world in linear perspective). Years later, when I learned to stitch together successive shots along the horizon I was somewhat more satisfied – but these photographic panoramas were a radical departure from linear perspective.

|

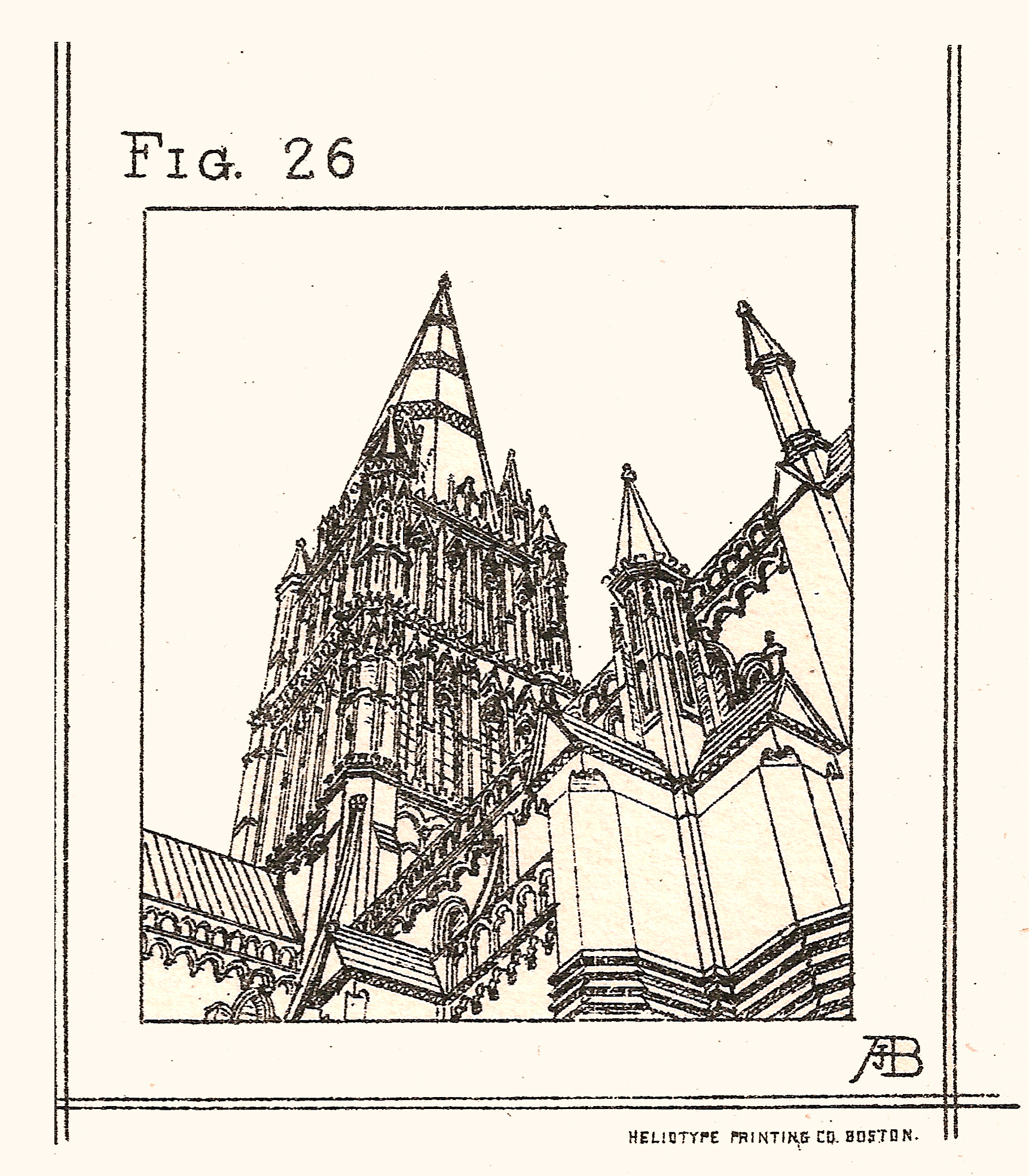

Figure 2 – Upward Converging Parallel Lines |

| Source: Ware, William R, Modern Perspective (Boston: Ticknor, 1882), Figure 26. This is the first image of upwardly converging verticals in a perspective treatise. Ware has copied the image from a stereoscopic photograph, "The Spire Of Salisbury Cathedral, Seen From Below," by William Sedgfield. |

Perspective is a way of representing the world neither as the world is in itself nor as we experience it. It represents things that we know to be the same size as radically different in size (note the desks in the displayed photograph in Figure 1). It represents lines that we know to be parallel as converging to a point in the infinite distance, just as the horizontal lines of the walls and floor of the atrium in Figure 1 do. Look closely and you will see that at that point of convergence there is a circle; I have cut it open as a peephole for reasons I will explain shortly.

Perspective distortions in an image look perfectly natural to us now, but they must have shocked people when Brunelleschi first depicted them in the early 1400s. I am confident of this because we have written accounts of how incredulous people were in the early 1800s when artists proposed a particular perspective distortion that had been avoided until then – upward converging parallel lines (Figure 2).[1] The principle is the same as for converging horizontal lines, however, many learned experts were convinced this was not how we see buildings when we look up at them and it was preposterous to represent them that way.

Brunelleschi dealt with incredulity by devising an apparatus to prove...

[1] For this evidence see Bantjes, Rod, "'Vertical Perspective Does Not Exist:' The Scandal of Converging Verticals and the Final Crisis of Perspectiva Artificialis," Journal of the History of Ideas 75, no. 2 (2014).