Bantjes, Rod, “Fraser_Mountain.html,” in Eigg Mountain Settlement History, last modified, 14 August 2015 (http://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/gis/txt/eigg/introduction.html).

Angus Malcolm Fraser (Eigg Mountain Settlement History) (Map Location)

Angus Malcolm [Ranald] Fraser (b. 1859-d.1947) was the son of Malcolm [Ranald] Fraser (b.1827-1899) and Ann MacArthur/MacIsaac (b.1829-d. 1893) and the grandson of old Ranald Fraser the pioneer. Angus Malcolm married Isabella (Bella) MacLellan (b.1870-d.1924) November 27, 1906 at Arisaig both born and living at Maple Ridge NSVS. (See obit). He appears in the following censuses:

1871 Census Arisaig District Division 2 #73

1881 Census Arisaig District # 35

1891 Census Arisaig District # 32

I am uncertain whether Angus Malcolm's father Malcolm [Ranald] established the farm at this site. Angus Malcolm Fraser lived here from at least 1871 until 1931 when he abandoned the farm and moved to town. This was shortly after his wife Bella died in 1927. They had no children. The Teasdales’ grandfather, Bella’s brother, continued to cut hay on these fields until 1933. The Teasdales’ mother remembers making hay here with her father.

|

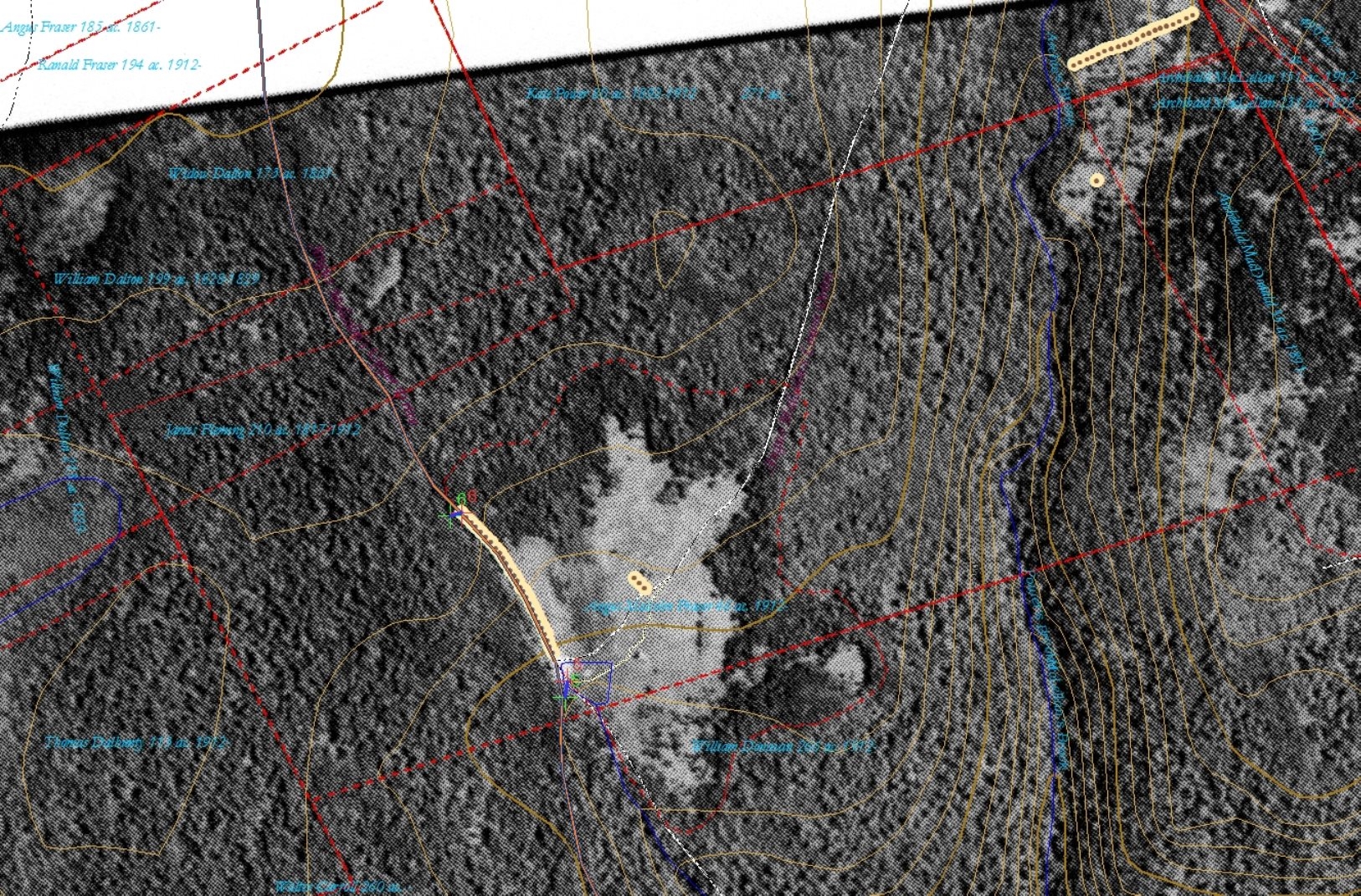

Figure 1 – Aerial photo georeferenced as a map layer. |

| The green and red “x”s joined by a blue line are control points that anchor features of the photo to features of the map. In 1945, when this photo was taken, the fields being filled in from the edges and the "succession" back to forest has begun. |

The aerial photo (Figure 1) shows what the field looked like growing in from the edges about 12 years after it was abandoned. The young white spruce or maybe alder show up darker than the mixed forests on the steeper slopes. Note that the hardwoods across Powers Brook to the east are also dark because they are in shade (the photo was taken in the morning). But the texture is coarser, showing the crowns of large hardwoods. Aerial photos were designed to be viewed in overlapping pairs through a stereoscope so that the contours and textures pop out in three dimensions. They cannot be viewed this way on the map,[1] so interpreting what they represent becomes a skill different from, but related to reading the forested landscape from the ground.[2]

I have removed the map symbol so you can see the house – its ridgeline running north-south with the east side of the roof in bright sun and the west side in dark shadow. It had been abandoned for 14 years at this point. It will continue to stand so long as the roof is intact. When a roof falls through, the whole building soon gives way and will show as a fuzzy white spot on a black-and-white aerial photo. (For more on how we used evidence from aerial photos to find farm sites see Finding Places or the notes on Allan Macdonald’s farm.) When we visited this site in 2004 it was covered in 60-foot spruce trees.

Angus Malcolm’s farm is a good example of how the land boundaries defined by use could be different from those defined by official survey. Whoever was the pioneer at this site (Angus or his father Malcolm) simply made a 46 acre clearing on a level, south-sloping spot. He defined his own boundary on the east by a road and a rock wall – this is a boundary that is not reflected in any land grant or survey. Then he carved out a picturesque, organic shape for the field – one that crosses an official boundary between lands granted to William Donavan and James Flemming. Both were probably absentee owners who held the grants as a speculative investment with the intention of selling them if the value increased. Neither person shows up in any of the census records. Flemming received the grant in 1817, well before settlement began in this area, and records indicate that he still held title in 1912 even though he was likely long dead by that time.

This and similar circumstances indicate that legal title to undeveloped lands in Nova Scotia in the 19th century meant relatively little in real terms. There cannot have been legal obligation to settle and improve the land as there was later for Prairie land grants.[6] Taxes apparently were not collected or at least not reliably since it seems unlikely that Flemming and his heirs would have paid nearly 100 years of taxes on land that they did not use and that was only worth a few shillings.[3] It was probably not until the 20th century that efforts were made to reconvey unused grants to the Crown.[4] Angus Malcolm and others who squatted on Eigg Mountain lands in the early years must have been aware of how little attention the state paid to matters of title.

Kenton Teasdale tells a humorous story about Angus Malcolm’s short stint as “school teacher” at Maple Ridge School. The actual teacher wanted time off to return home one Easter and Angus Malcolm offered to look after the kids. He pulled some stunt to entertain them, the details of which I cannot remember. What I do remember was Kenton insisting that Angus Malcolm “never had a day of school in his life.”[5] The schoolhouse was close by to his family’s properties, so why would he not have been sent to school in 1865 when he was six? Children’s labour was needed as soon as they could work, but not so much during the winter. It is possible [this would not be hard to check] that the school did not yet exist in the 1860s.

|

Figure 2 – A portion of the stone cellar wall. |

| Photograph taken Sunday, November 7, 2004 |

Angus Malcolm’s house foundation is situated near a stream flowing through a wetland in a valley sloping gently to the southeast. What is left is a large two-chambered cellar measuring 16 ft. x 40 ft. The center wall apparently followed the ridgeline. The rectangle is oriented at 291°, or west-northwest. The south corner gives evidence of the direction the building faced. Here the wall turns out, probably for cellar steps to the outside (and probably to the back of the house). If so the house would have looked back up the mountain across the brook and towards the road coming down the edge of a former field. Across the “front” of the house I can only find evidence of 28 ft. of foundation (perhaps the building was l-shaped).

|

Figure 3 – A portion of the stone cellar wall. |

| These hard, irregular stones are difficult to build with. Photograph taken Sunday, November 7, 2004 |

The stone (Figure 3) is like a blue slate that sheers into planes that are rarely flat on more than two faces and rarely meet at right angles. It takes considerable skill to build anything lasting with recalcitrant material such as this (for another example of difficult Eigg Mountain stone see a cellar in the back settlement). For much better Eigg Mountain stone see Colin Col MacDonald’s. For examples of flat fieldstone, mostly sandstone, that is easier to assemble into walls see a MacIssac foundation and a Gillis foundation from Georgeville, and a MacIssac foundation from Cape George. Both digging basements and building walls were often harder on the Mountain than elsewhere.