Bantjes, Rod, “Aerial_Photos.html,” in Eigg Mountain Settlement History, last modified, 14 August 2015 (http://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/gis/txt/eigg/introduction.html).

Working with Aerial Photos (Eigg Mountain Settlement History)

There were two main series of aerial photos that we used to make the map. The first was from a fly-over in 1945. It was a government effort flown by R.C.A.F. pilots, no doubt with experience from the Second World War where aerial photography was of strategic importance. It formed the basis for the first topographical survey map of Nova Scotia (the Antigonish sheet published in 1951).

|

Figure 1 – Passage of Time, Arisaig Series (1951). |

| In these successive aerial photos you can see the progress of a truck as it makes its way along the shore road near Arisaig. In the time it took to pass a side road, the plane, watching from overhead, covered about the distance you can see in the image from right to left. For the first time many farmers would have been able to afford trucks and tractors, but even in this series of photos it is rare to see them either parked in the farmyards or on the roads along the gulf shore. All the Eigg Mountain farmers had abandoned their land by this time and tractors, trucks and good gravelled roads would have been an impossible dream for them. |

The second series of aerial photos was made through the geology program at St Francis Xavier University.[1] The StFX photos only covered a limited area of the Eigg Mountain map (a strip near the Northumberland Strait), but the plane flew lower than in the 1945 series and the images are for this reason amazingly detailed and very evocative of the day in 1951 when they were taken (see Figure 1).

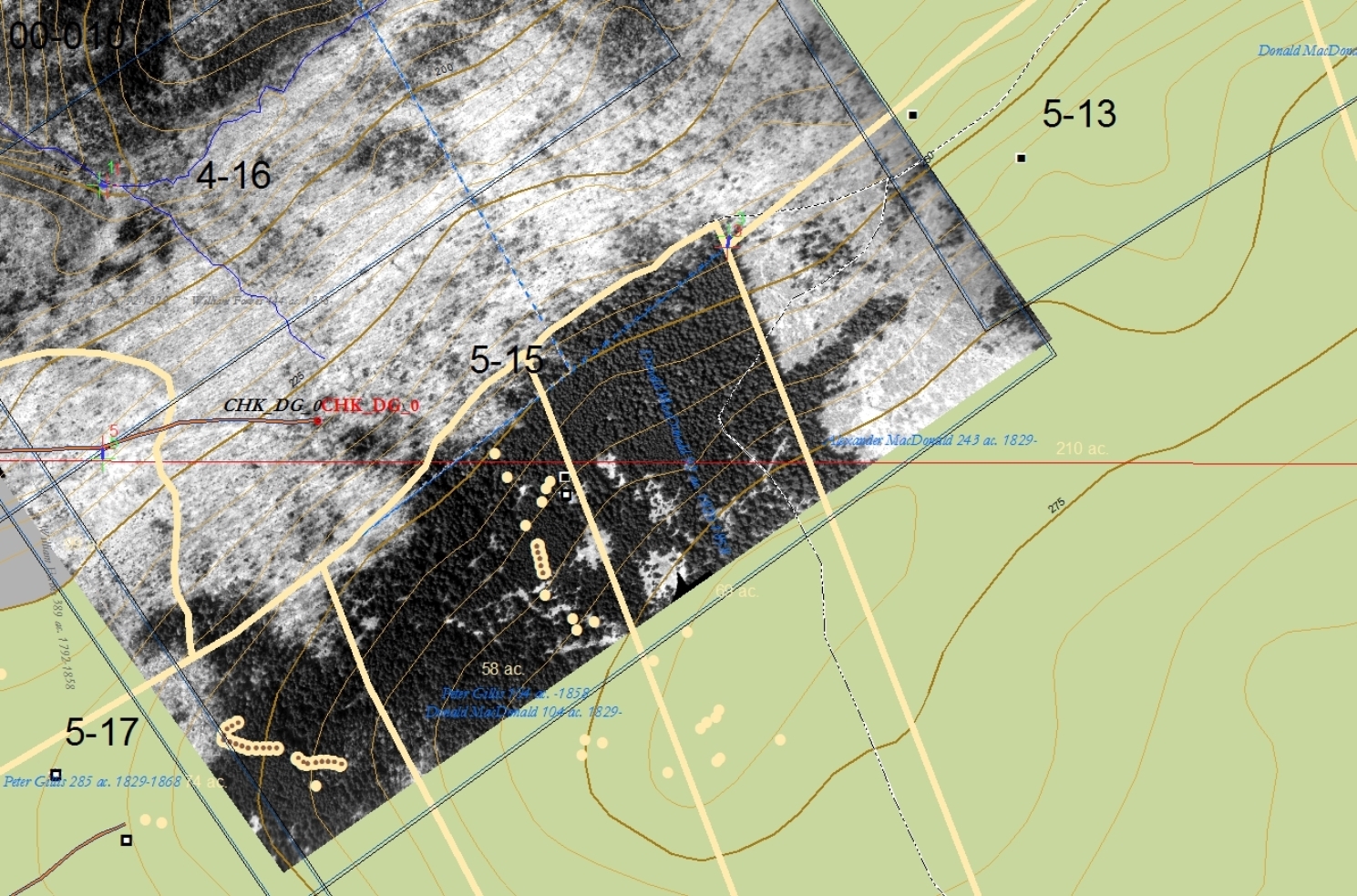

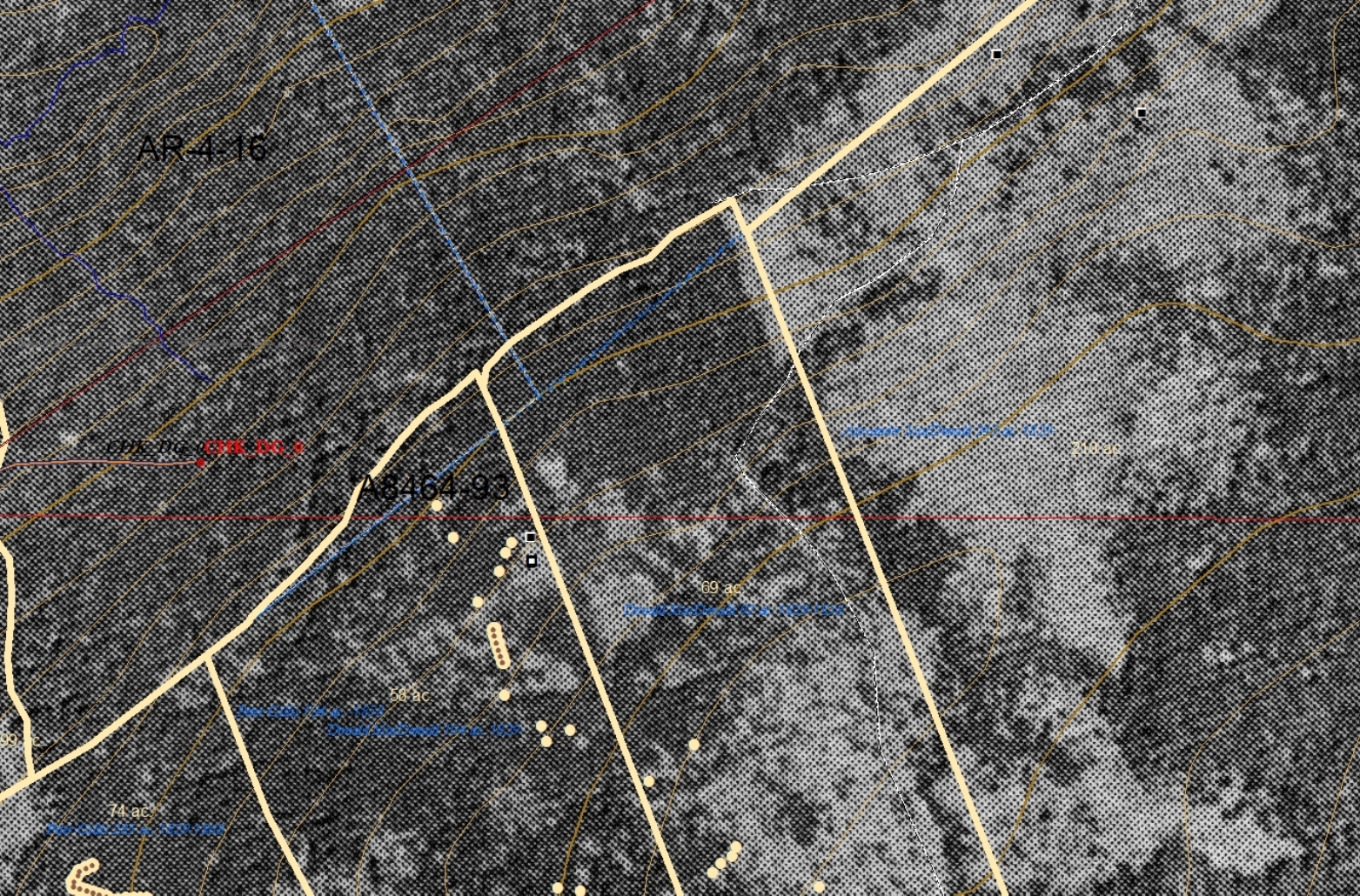

In order for aerial photos to be useful for our project we had to georeference them to the base map. Fitting features in the photos to features on the map is like assembling a jigsaw puzzle – it involves being attuned to patterns where you only have fragments and where the orientation and scale are distorted. Once you have found where a photo goes, you pin it (or rather a scanned digital version of it called a “raster”) to the base map with control points that show up as little green and red “x”s. The match is never perfect and sometimes the control points twist and skew the photo as though it were made of elastic. Blue lines indicate tension between the control point on the map and that on the photo. Once the photo has been georeferenced, the base map can identify the precise location in longitude and latitude of any feature represented on it.

|

Figure 2 – Georeferenced aerial photo from the Arisaig series (1951). |

| Even-aged stands of softwood show up as dark areas with a relatively dense, homogeneous texture. This is how forest overtakes former fields. The mixed forest to the north evident in the 1945 photos (see Figure 3) has recently been cut for lumber. |

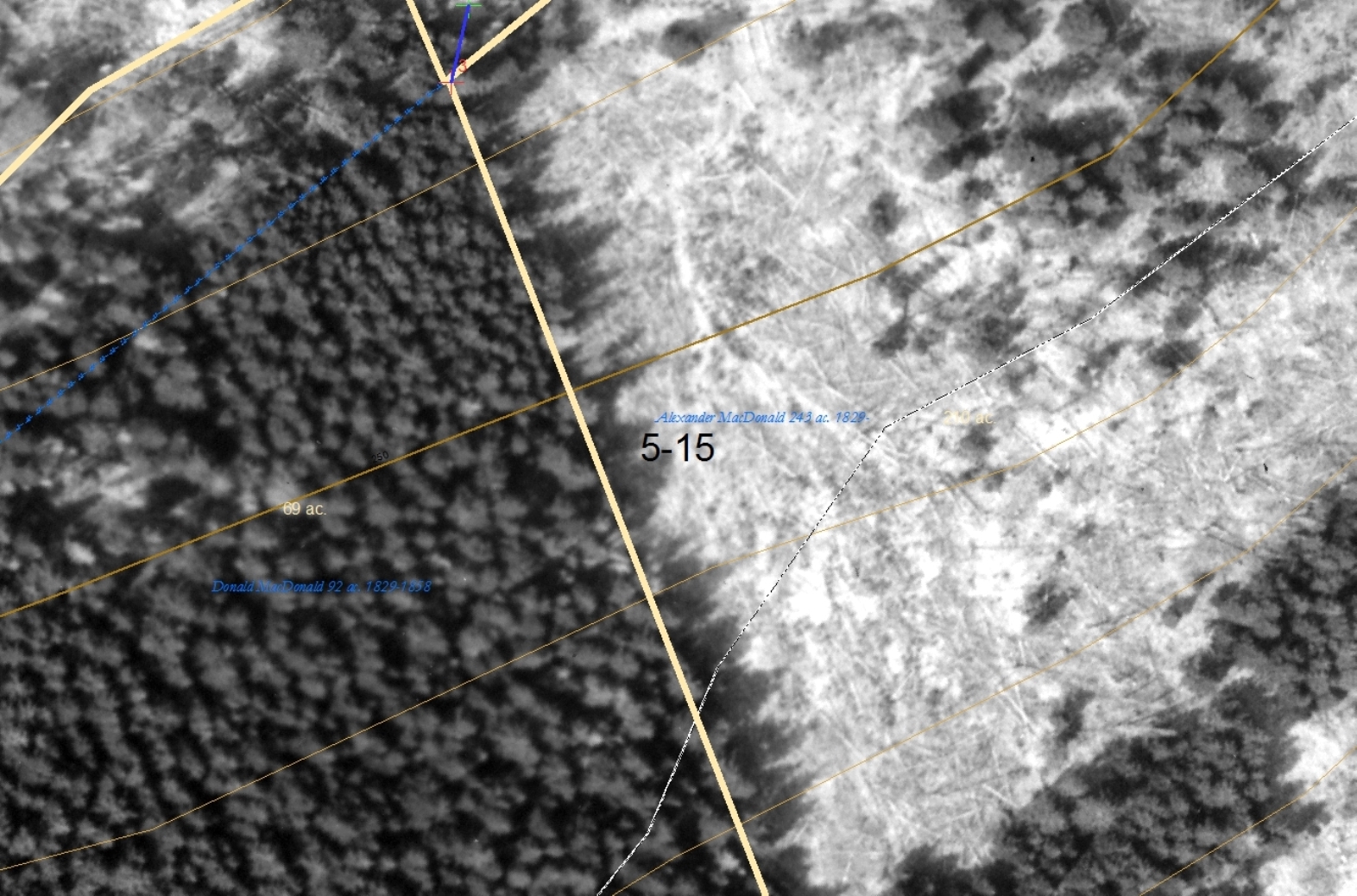

Figures 2 and 3 are examples of how we used georeferenced photos to identify old fields. (See Angus Malcolm Fraser’s field for another example.) Figures 5 and 6 (below) show how we used them to identify the remains of houses and barns. I use the example of Allan MacDonald’s farm to show how the georeferenced photos helped us take the further step of finding things in the landscape. Any feature we see in the photo that we think might be interesting to check out on the ground, or else a path that we want to follow through the woods I mark out with points labelled “CHK_...” These points on the digital map can be transferred to the handheld GPS unit. When we are in the woods, the GPS can guide us to where things represented in the photo were actually located in the landscape. This is the closest one can come to actually stepping into the world depicted by an historic photograph.

|

Figure 3 – Georeferenced aerial photo from the 1945 series. |

| Here is what the same area (as Figure 2) looked in a low-quality scan of a photo from the 1945 series. The difference between the softwood to the south and hardwood or mixed forest to the north is very subtle (the softwood has a more dense texture) and the line is hard to draw. In the three plots to the left the light areas indicate land that is still open and grassy. The fact that these areas were once fields is confirmed by evidence on the ground of rock piles and walls. |

Reading aerial photographs for evidence of land use can be treacherous. In Figure 4 you can see clearly the even-aged stand of spruce on the left of the sand-coloured line. Not only are the pointed tips visible from the top, but you can see them in profile in the shadows cast on the ground. They are probably 40 – 60 feet tall which means that this field has been abandoned for a long time – I would guess since 1890. I am pretty sure that there was a field on the right of the sand-coloured line since I know there were farm buildings near here on this property. But what appears to be open grassland in the 1945 photos is revealed here to be recently cut forest – you can see tree trunks strewn on the ground. So here, what appears in the 1945 photos as forest is actually former field and what appears to be field is actually former forest. To confirm that the forest on the right was at one time a field would require a ground survey. Land use was changing in the 1940s. The prevalent human activity was harvesting and milling wood. Sawmills, beside huge sawdust piles evident as white pimples from the air, were common across Eigg Mountain. This new layer of activity was obscuring traces of the previous one.

|

Figure 4 – Close-up of Softwood Stand and Forest Harvesting. |

| Much higher definition is possible from the 1951 Arisaig series. Here you can tell from the felled trees that the right-hand area is a forestry operation, not a field. The spruce trees on the left of the line have grown up in a former field. |

|

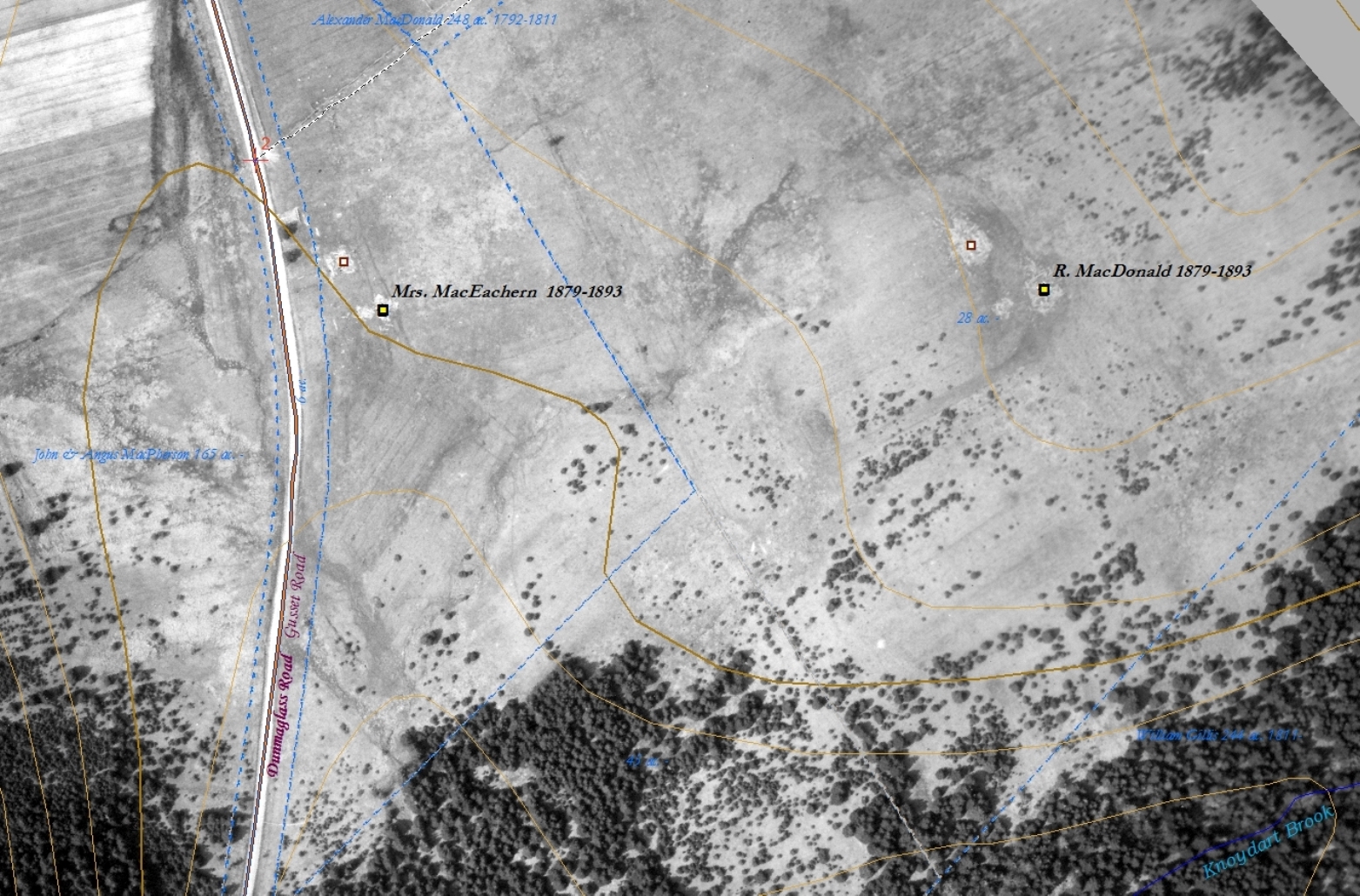

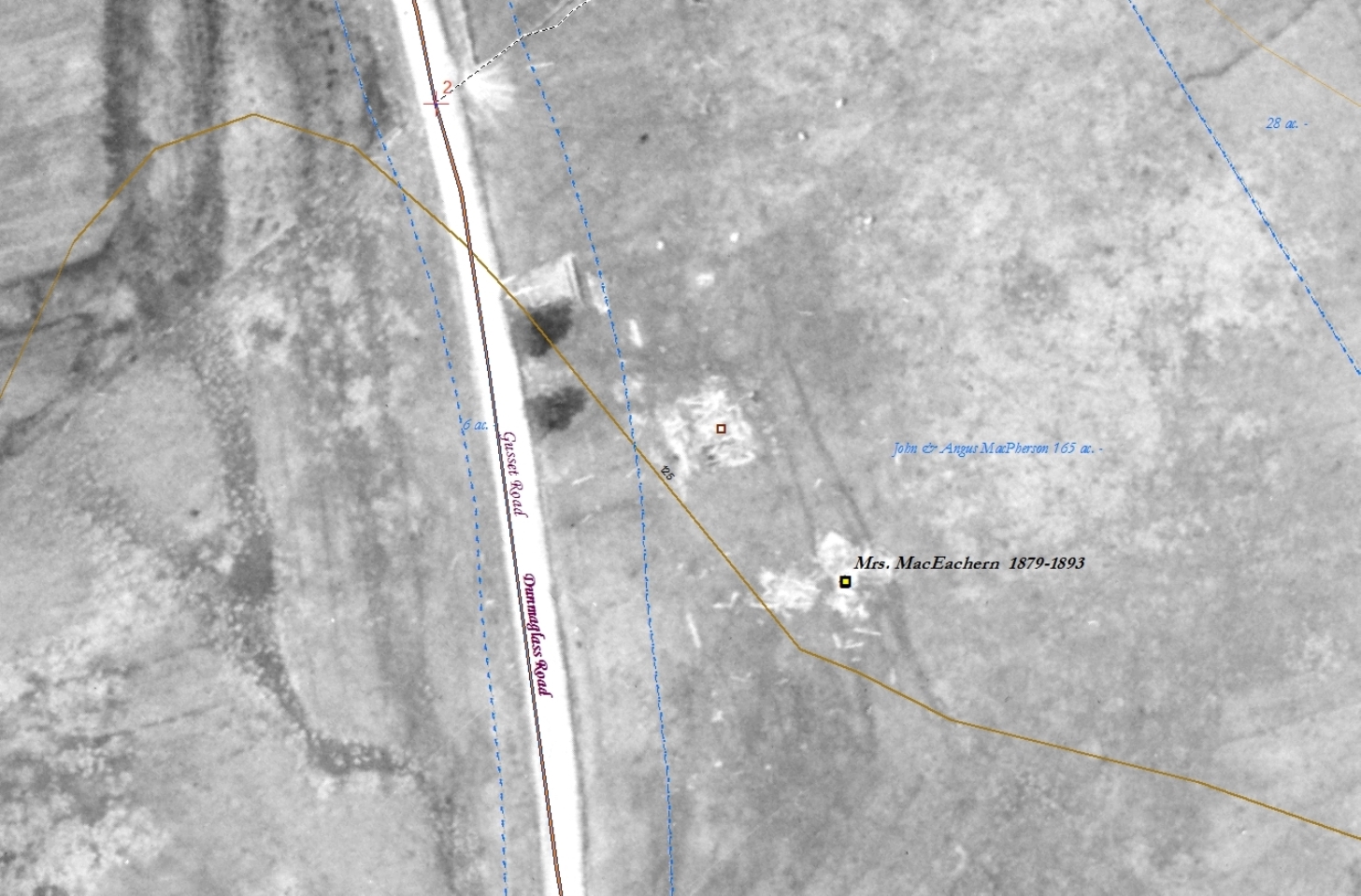

Figure 5 – Georeferenced aerial photo from the Arisaig series (1951) showing abandoned farms. |

| Note how the lines of furrows are clearly evident in the fields in the upper left-hand corner of the photo. The vegetation that grows up in abandoned fields follows the furrows – you can see the roughly linear pattern in the MacDonald and MacEachern fields and in William Fettle’s field (Figure 7). |

|

Figure 6 – Close-up of collapsed buildings in an aerial photo from the Arisaig series (Figure 5). |

| In the 1945 series collapsed buildings show up as fuzzy light spots; here you can actually see the old beams strewn around. These buildings appear on the Church map (1878) and Geological Survey map (1886). I have repositioned them based on this aerial photo. This site is on the map, but not on Eigg Mountain proper – in such cases Charlie Teasdale and I have not attempted to find the old foundation. |

|

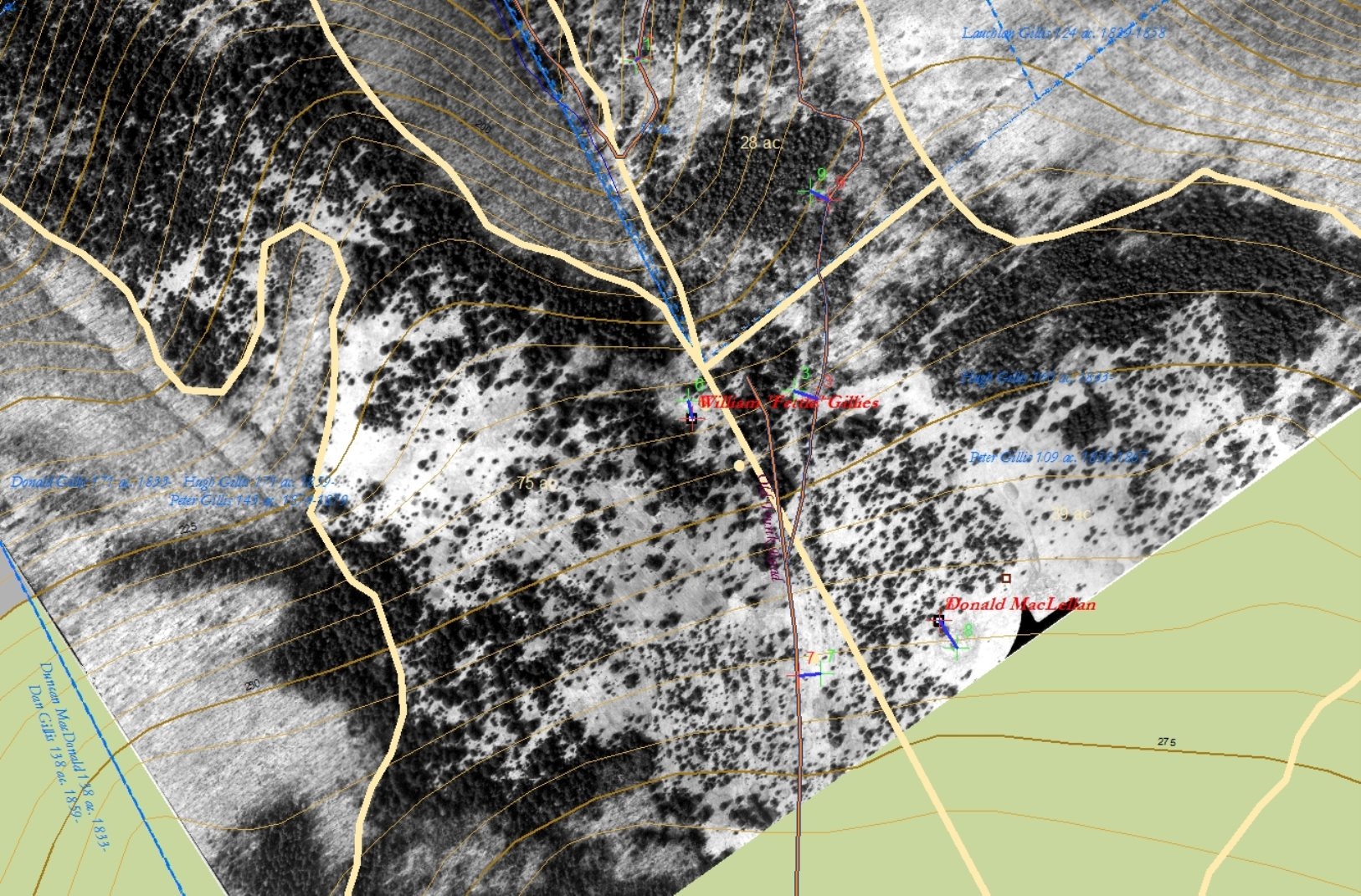

Figure 7 – William Fettle’s fields on the Arisaig series of aerial photos. |

| Note the linear pattern in a small square near the bottom of the photo. This was a cultivated field, about 3 acres in extent, its furrows oriented downhill parallel to the road. Most of Fettle’s fields that extend downhill on a fairly steep slope to the upper left of the photo were probably pasture – cleared but not cultivated. The fact that they did not have to be repeatedly ploughed would minimize erosion. Fettle probably fertilized the cultivated field with manure from the livestock – a transfer of nutrients from pasture to cropland.[2] |