Bantjes, Rod, “Soil_Fertility.html,” in Eigg Mountain Settlement History, last modified, 14 August 2015 (http://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/gis/txt/eigg/introduction.html).

Eigg Mountain Soil Fertility (Eigg Mountain Settlement History)

The story that my students and I wanted to test on Eigg Mountain is one that has played out many times in human history. Vernon Carter and Tom Dale outline it here in their 1955 book Topsoil and Civilization.

Civilization spread from the irrigated valleys to other areas. In most cases those other areas did not have the conditions that stabilized the Nile Valley, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley. The soil was fertile, but much of the land was sloping, and rainfall furnished the water for crops. When the rains came, they washed away the fertile topsoil from the sloping grainfields, deforested hillsides, and overgrazed grasslands. The land was often ruined for farming in a few generations.[1]

Unsustainable land use, they argue, has led to the fall of between “ten to thirty different civilizations.”[2]

The Eigg Mountain story is not one of the collapse of civilization, but certainly of the abandonment of agricultural settlement after only about three generations. We do not know the agricultural conditions that the Irish settlers experienced in Ireland, but we do know that the Scottish settlers came from marginal highland country already under stress from overuse. “Erosion,” according to Carter and Dale, had become “acute” in the Scottish highlands “during the latter part of the eighteenth century.”[3] While Eigg Mountain and other highland areas in Antigonish County may have recalled landscapes that they loved, settlers must have recognized the difficulty of cultivation and chose these areas last. They settled first along the lowlands of the Northumberland shore, and even traversed the Mountain into Pleasant Valley, carved out of its southeast edge by the Wrights River, before trying their fortunes on the highland plateau.

|

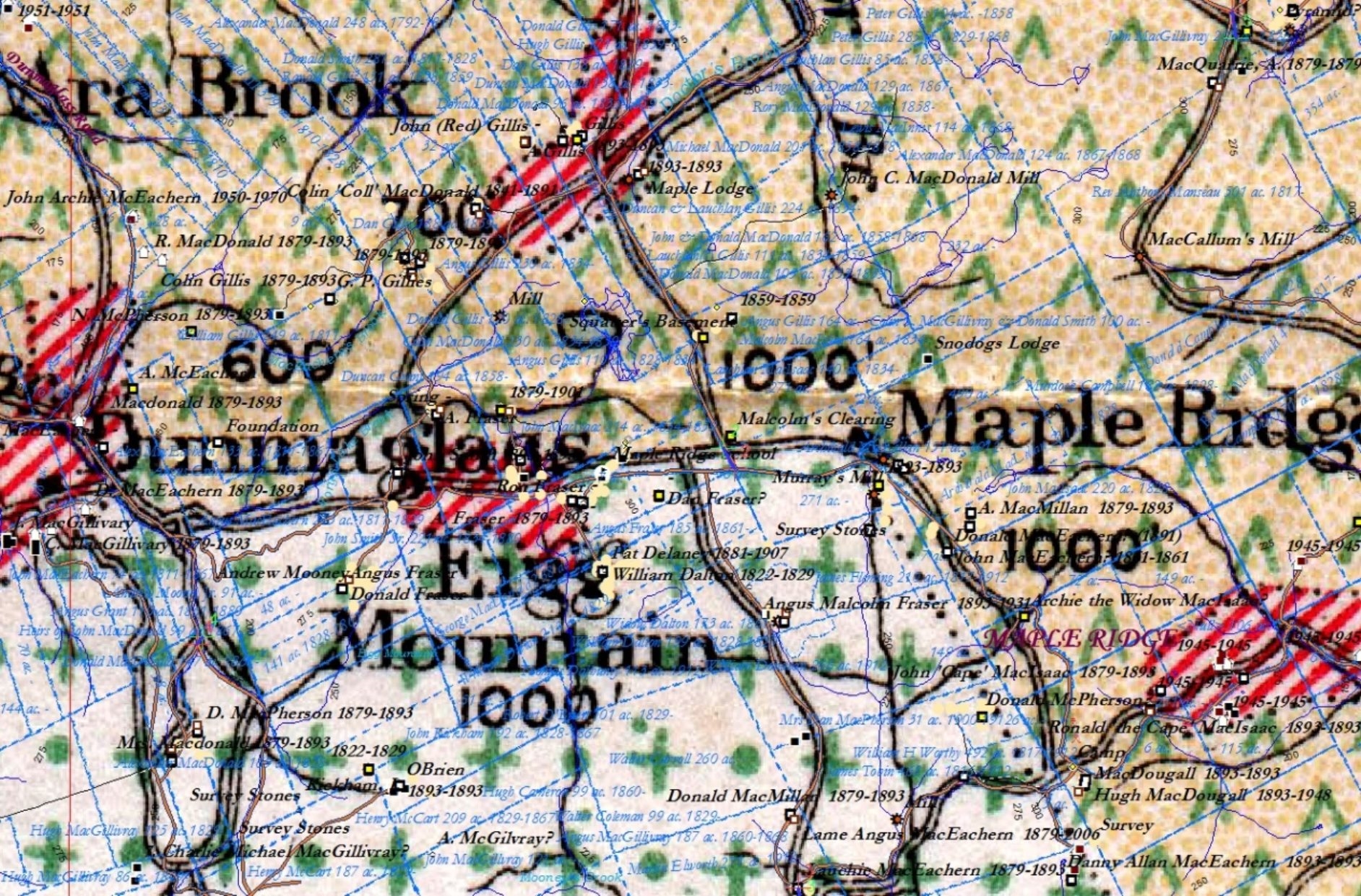

Figure 1 – Fernow’s Map of Forest conditions, 1912, georeferenced to the ArcView map. |

| The green arrows over tan dots represent young growth; the green dots and crosses on white represent severely culled mixed forest and the red stripes represent farmland. The survey boundaries were rather crude since there are field areas that we know of from other evidence that are missing here. |

There deforestation had already begun. Many of the finest trees of the Acadian old growth forest had already been felled to supply the British shipbuilding industry.[4] By the time the first settlers arrived, finding a tree fit for a mast was a rare event, one that Rev. Ronald McGillivray thought worthy of retelling in 1892.

John Smith found a pine tree that was 88 feet long, ten inches in diameter at the top end. He sold the tree to the Pattersons of Merigomish (for a spar) for the sum of 18 pounds. Donald McGillivray sold two trees or spars to the same men for 18 pounds. They had fifty pairs of oxen hauling the three spars to the Cove, and 20 gallons of Jamaica Rum.[5]

There are no pines left on Eigg Mountain, and it would be difficult to find any tree taller than 60 feet.[6] When the Canadian Commission on Conservation surveyed the province in 1912, the forested areas of Eigg Mountain were listed as “severely culled” or “young growth,” presumably after having been completely cut over.[7]

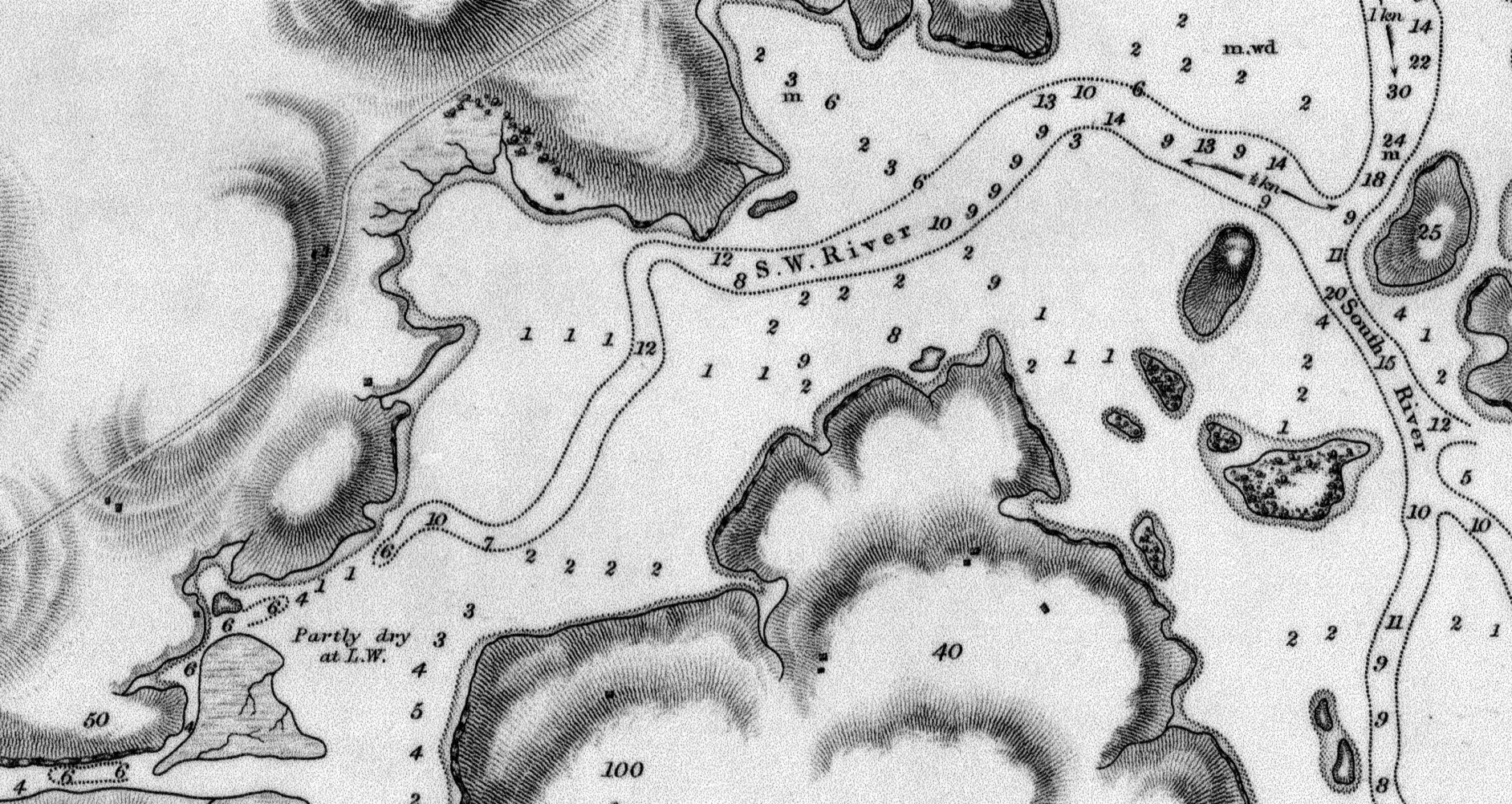

Deforestation from logging and clearing for agricultural land, not just on Eigg Mountain, but in the whole of Antigonish County did lead to erosion. Siltation in Antigonish Harbour is one indicator of that. The Harbour is the drainage basin for most of the County, and captures about half of the precipitation from Eigg Mountain flowing down through the Wrights River. Vessels of up to 60 tons were once able to dock at the Landing at the head of the Harbour.[8] As early as 1864, long before the furthest extent of land had been cleared for agriculture in 1891,[9] the channel to the Landing had to be dredged and thereafter repeatedly re-dredged until the project was abandoned as hopeless.[10] Siltation has since eliminated the channel (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 – Detail of Captain H. W. Bayfield’s Map of Antigonish Harbour, 1845. |

| The channel to the Antigonish Landing, marked “S. W. River” no longer exists as a channel, that is, as a navigable route at least 6 feet deep at normal low tide. (Soundings here are measured in feet.) The siltation of the channel is evidence of erosion from the surrounding farmland. However, this harbour has always been shallow and far from ideal for shipping. |

The settlers of the highlands of Eigg Mountain may not have been any more responsible than others for the flow of topsoil into the harbour. They came with the accumulated skill and knowledge of many generations who had made their livings in the harsh conditions of the highlands of Scotland. They had already learned from the mistake of tilling the steepest slopes.[11] On Eigg Mountain they chose instead the high plateau or small secondary plateaus on the downward slope. The farms of Andrew Mooney, Angus Malcolm Fraser, Donald MacMillan, Laughie MacEachern and Allan MacEachern are all examples of this choice on the south slope of the mountain. They had a unique understanding of soil. Some were reputed to be able to assess the mineral and nutrient content of good soil by its taste.

For the first few years they benefitted from the ancient technique of slash and burn agriculture. After the heavy work of clearing, the wood and debris that they didn’t use for building or firewood they burned on site. This released the accumulated nutrients from the forest canopy into the soil and boosted fertility for the first few years. They dug in among the stumps and stones, probably with a caschrom,[12] and planted potatoes and wheat. The first yields according to J. W. Macdonald, were “often enormous.”[13] They probably shifted crop production to benefit from these windfall yields as they expanded the cleared area and worked at removing the stumps and stones. Eventually they would focus crop production in the best soils and leave the rest to hay and grazing lands.

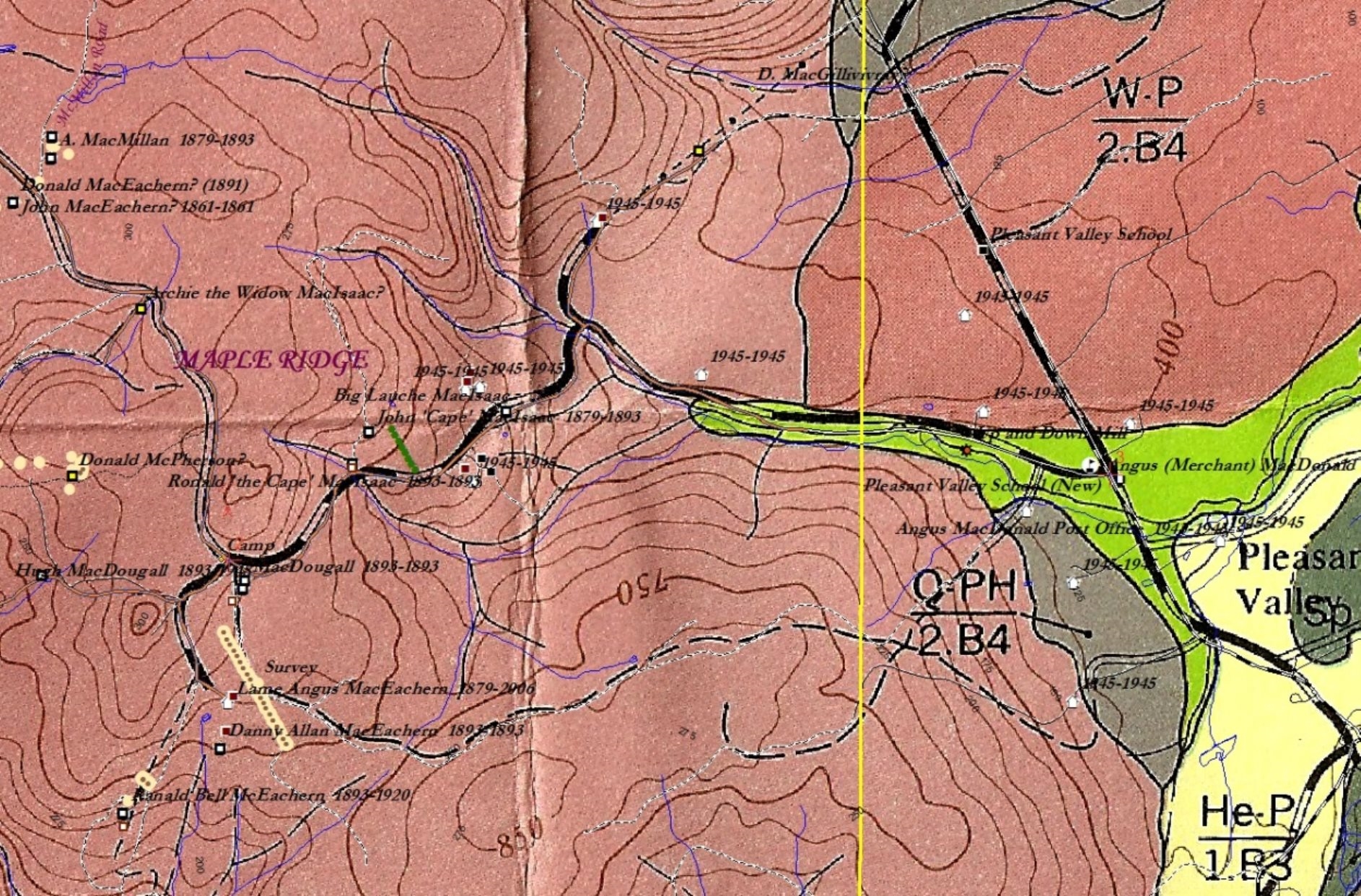

The soils that they had to work with were some of the poorest in the County. A survey of soils done by the Federal and Provincial Departments of Agriculture in the early 1950s categorized the entire Eigg Mountain area as Thom catena, with the code, TM-P/3.B4. The authors recommended against cultivating Thom soils, concluding that “some areas are suitable for grazing with proper fertilization and management, but forest is the most suitable crop for a large part of these soils.”[14] However, they may have been overgeneralizing. For example, the authors describe the till of Thom catena as “usually shallow.”[15] But we found that that was not always true in places like the Mooney/Fraser field. Settlers were no doubt aware of the challenges their chosen soil posed, but sought out the few choice exceptions to the general poor quality. They may have found plots with less “irregular or rough surface[s],”[16] more depth of humus, less acidity, and fewer rocks than the average. Rocks though were hard to avoid. The number 3 in the code TM-P/3.B4 indicates “sufficient stone to be a serious handicap to cultivation.” The number of rock piles, some of them massive, scattered throughout former fields, attest to this handicap. The Soil Survey characterization of Thom catena as “sandy loam; granular structure; friable; numerous angular stone fragments”[17] is about right for many of the fields we uncovered.

|

Figure 3 – Soil Survey map (1953) georeferenced to the ArcView map. |

| The yellow line is the eastern boundary of our Eigg Mountain map. West of the line all soils are characterized as TM-P/3.B4 (Thom). The bright green area east of the line represents Stewiacke soil (Se-P/0.A2), very fertile alluvial deposits washed down from the highlands. Note that the farm dwellings near the better soils still existed in 1945 (they were added to the map from aerial photos of that year), those on the Thom soils were mostly gone, and those at the higher elevations were all gone. |

The authors of the Soil Survey lend support to the idea that soil quality made farming unsustainable. “Thom soils” they write, “support good forest growth” only when protected by the forest canopy which cools the surface, keeps it moist, and, along with the tree roots, protects it from the erosive force of heavy rains. However, these soils

deteriorate quickly under cultivation, particularly on the hillsides. The porous nature of the soil and its hilly topography result in too rapid drainage and in dry years the crops suffer from lack of moisture. ...Erosion is severe on many of the steeper slopes and gullying is evident in many places.[18]

Rev. Ronald McGillivray who observed the Eigg Mountain farms in the late nineteenth century, also, despite his evident sympathy with the farmers, implies that they had chosen to cultivate unsuitable land. They had already experienced “partial failure of the crops” for “several years now,” a fact he attributes in part to soil quality and a decline in fertility.

The early settlers on the mountain were once in good circumstances. The virgin soil was good, and they were tireless workers. One can see on the farms the great cairns of stones which their industrious hands piled up. I am not without sympathy for the present inhabitants: their lines are cast in hard places. The soil is light, dry and stony.[19]

Then McGillivray points to another factor that may have been more decisive in the fate of the settlement. “Early frost,” he writes, “damages the crops.” The Isle of Eigg from which many of the settlers emigrated, is, like its namesake a high plateau, higher in fact than Eigg Mountain. Experience must have told settlers that this terrain was manageable. They surely realized that a higher elevation meant a cooler climate, but on the Isle of Eigg, warmed as it is by the waters of the Gulf Stream, that would not have resulted in deep, persistent snow cover. On Eigg Mountain the snow can linger into late May. McGillivray notes that “in the month of April last, when the roads at the shore were dry and solid as in June, I have seen the mountain roads covered with three feet of snow.”[20]

Persistent snow may have hampered the settlers’ ability to fertilize their field crops and gardens. McGillivray gently chides the younger generation to do more in this regard.

There is much more in the soil than we coax out of it. Intelligent labor can overcome many unfavourable conditions of soil and seasons. Be kind to the soil and give it food and cultivation for the bounties it yields you.[21]

His advice is consistent with “modern” ideas of the late nineteenth century about agricultural improvement. Soil was to be understood not as given by nature but as an artefact that could be transformed and improved through science and technology.[22] The new agricultural experts often underestimated the extent of traditional farmers’ practical understanding of the principles of soil amelioration.

Highland farmers in Scotland had for generations practiced a system of nutrient cycling adapted to poor soils. The cycle depended upon livestock that could be set out to graze on extensive tracts of pasture where the soil was too poor for growing crops. Eigg Mountain offered ample lands of this type. Animal manure could then be collected and spread on select fields intended for oats, wheat or other food crops. In this way nitrogen and phosphorous could be “harvested” from a wide area and concentrated on small portions of arable land – as little as 15 to 20% of the total acreage in sustainable systems in Scotland.[23] The trick was collecting the manure. The Scots did this in winter by bringing the animals to “sheltered winter grazings, including the grass growing on balks between rigs, plus the winter feed supplement offered by hay meadows and straw.” They also were known to keep animals “indoors over night, and, in some cases, during the day so as to collect their manure.”[24] The balk was an unploughed ridge that in Scotland could be relied upon to be bare of snow. However, winter grazing on Eigg Mountain was not possible. All forage would be buried under three to six feet of snow, so farmers would have had to depend solely on the straw collected from their grain fields and hay from the pastures.[25]

All of this fodder had to be cut by hand and stored in the barn. Barn size made a difference (both for feed storage as well as manure collection, if animals were to be kept indoors). But farmers also had to collect more fodder than traditional practice had prepared them for. That fodder also had to last far longer – until the snow cleared. The same amount of pasture supported fewer animals; and fewer animals meant less nutrient cycling. Farmers probably were already feeding the soil, just as McGillivray advised, and they were probably expending even more labour than their ancestors had in doing so.[26] But traditional practice had met with an unanticipated obstacle in the form of the Canadian winter at high elevation. This is at least a plausible speculation that the census records might confirm if one were to compare farms on the mountain and the shore with respect to acres in field and pasture and numbers of livestock.

|

Figure 4 – Cas-Chrom in use on the Isle of Skye. |

| This implement has a long, often steel-reinforced tip and a peg to brace the foot against when driving it into the soil. Source: "The Silver City Vault – the online collections of Aberdeen Local Studies." |

Scottish highlanders employed other, more direct methods of improving the quality of their soil including carting and spreading “shell sand [to reduce acidity], seaweed, peat, peaty soil, turf, and heather.” Antigonish farmers near the shore were known to use seaweed, but it was understood to be a “quick fix”[27] without lasting fertility effects – a defect that would not have justified the long haul up the mountain. While this is probably not what McGillivray meant by advising more cultivation, the old Scots also knew that they could increase yields by “more labour-intensive cultivation...using the spade and caschrom instead of the plough.” While the Eigg Mountain people may have employed the caschrom, a kind of hand-plough best suited to working soil in between stones (figure 4), the further demands of time and toil might have stretched them to the limit.

McGillivray calls on them to improve the look of their fields, almost as though their ragged appearance showed lack of effort or self-respect.[28]

Clear away off your farms those unsightly piles of stones into some invisible Hades, or make fences with them. Take a pride in having a nice, clean farm. The honest, tireless hand will always have enough for its own needs and a little surplus for the claims of charity and hospitality too.[29]

Many did arrange their fieldstone into walls, or at least straight boundary lines.[30] However Eigg Mountain stone is not easy to build with unless carefully selected and meticulously fitted with small angular support stones.[31] People had neither time nor resources for this fine work on such a large scale. They relied on split rail fences to keep livestock from wandering.[32] Given the scale of the challenges they faced, they had to direct their energies wisely. They had to work harder than people in the valleys just to keep the land viable.

If I am correct, then the crop failures of the 1880s and 90s were mostly the result of declining soil fertility. That decline was caused, not primarily by erosion or poor soil management practices as most commentators think. Instead, farmers applied old soil conservation practices which involved cultivating only choice fields on level plateaus and cycling nutrients to these fields from pasture that had to be mowed but not cultivated.[33] In this way they minimized erosion. While they also struggled to build soil fertility, their efforts were confounded by the uninterrupted snow cover of the long mountain winters. This in itself might be enough of an “ecological” reason for the eventual abandonment of settlement.

The traditions that farmers brought with them to the New World had worked, with some modifications, since ancient times, but they were developed for agricultural subsistence. They were displaced from the highlands of Scotland largely by the pressures of market-based agriculture. A similar movement in late nineteenth-century Canada placed intolerable strains on the subsistence model. Traditional farming relied on tremendous expenditures of labour, both animal and human. Efficiencies were found not through labour-saving machines, but through social co-operation. The tradition of the “frolic,” or community work gathering, was kept alive in Antigonish County.[34] In frolics for ploughing, wood cutting, harvesting and building, the collaborative action of many hands increased productivity, and a spirit of community and merriment, perhaps unintentionally suggested by the name, lightened the work. Subsistence agriculture benefitted from intact communities and individual farm households benefitted from large numbers of children who could contribute to the common labour.

To break from the subsistence model, farmers had to produce surplus food that they could sell to market at competitive prices. With the opening of the prairie west to settlement in the early twentieth century, market competition intensified. Prairie agriculture was market-oriented from the start and on a trajectory towards increasing capital investment in machinery, land and eventually in artificial chemical inputs to boost soil fertility. Maritime farmers could raise capital by working off-farm for wages (having many working-age children was an asset here as well) or forming co-ops.[35] But always, farms like those on Eigg Mountain with the poorest soils, the harshest winters, on tortuous roads, and distant from markets, were at the tail end of this scramble to modernize. The temptations for young people, especially for those working off the farm, to leave for better opportunities in the West or in the wage economy, were often too strong. When young people left, the crucial labour pool was diminished and subsistence settlements like Eigg Mountain entered a self-reinforcing cycle of decline.[36]

What I am arguing here is that, even without competition from an industrializing economy, even if subsistence were the only option, highland settlements like Eigg Mountain could not have survived for many more generations because, despite their best efforts, farmers were not able to maintain soil fertility.