Bantjes, Rod, “Making_Claim.html,” in Eigg Mountain Settlement History, last modified, 14 August 2015 (http://people.stfx.ca/rbantjes/gis/txt/eigg/introduction.html).

Making Claim to the Land (Eigg Mountain Settlement History)

You might think that determining who owned what and when on Eigg Mountain would be fairly straightforward. However, the official records from the 19th century of land descriptions and land transactions are surprisingly inaccurate and incomplete and often bear little relation to how people actually used and made claim to the land. The sorry condition of legal records says something about the capacity of the state to define and manage land claims, and more generally, to govern in places like Eigg Mountain in the 19th century.

In the European tradition only sovereigns had the power to grant title to land. That title gave the property owner a limited bundle of rights to use, improve or sell the land, rights that in many instances could be circumscribed at the pleasure of the sovereign. It is still the case in Nova Scotia that the “Crown,” or the sovereign authority of the state, retains mineral rights and can expropriate land for right-of-ways for roads, power lines and the like. “Sovereignty” then, is a governing power that enables its holder to constitute and supersede ownership. European sovereigns gained this power over new lands through conquest, which is a grand term for theft through violence, or else by treaty with those in possession of sovereignty.

|

Figure 1 – Mi'Kmaq Encampment c. 1850 |

| The Mi'kmaq are the first claimants to these lands. While they ceded rights of use to settlers, they did not cede what the Europeans understood as "sovereignty." Image source: Unknown Artist, c. 1850, Micmac Indians, oil on canvas, 45.7 x 61 cm, National Gallery of Canada. |

The Mi’kmaq people had inhabited Nova Scotia, or as they called it Mi’ma’ki, for thousands of years before Europeans arrived, so if anyone could claim sovereignty or confer it to others, it was the Mi’kmaq. In the 18th century when the French and the British were competing for dominance in the New World, the Mi’kmaq were of strategic military importance. Neither of the European powers had the capacity to conquer them, and both feared that the Mi’kmaq would form a military alliance with their enemies. So the British entered into treaty with them in a series of so-called “peace and friendship treaties.” The British wanted the Mi’kmaq to remain loyal in any military conflict and to allow settlement to advance unhindered. The only wording in the (1726) treaty relevant to land claims is worth quoting in full: “the Indians shall not molest any of his Majesty’s Subjects or their Dependents in their Settlements already made, or Lawfully to be made...”.[1]

While later treaties entered into by the Dominion of Canada with aboriginal peoples in the West contained wording which explicitly “extinguished” aboriginal title to land, the Peace and Friendship Treaties did not. Nor did they explicitly confer sovereignty over the Mi’kmaq people or their lands to the English crown. The two parties had different understandings of what it might mean for new settlements to be “lawfully” made. Legal historian William Wicken has surveyed surviving documents from the period which give insights into Mi’kmaq understandings of what the treaties meant. The Mi’kmaq attitude seems to have been “there is ample room here for everyone: you do your thing in peace and we will continue to do ours as we have done from time immemorial.” “Sovereignty” was not a Mi’kmaq concept, and they were not of the understanding that they had granted its powers to others. They did not think of themselves as subject to the supreme authority of the British Crown, nor did they cede to the Crown a unilateral right to dispose of land within Mi’ma’ki.[2] By “lawful” settlement they probably imagined some process of mutual agreement in which Mi’kmaq permission was essential.

British authorities, perhaps through willful misunderstanding, acted as though they had a unilateral, sovereign authority to grant title to land, which they began to do in the Eigg Mountain area in the early 1800s. By this time, had the Mi’kmaq been consulted, they might have shown little interest. From their perspective, if one were to settle for any length of time the choice sites were the coastal inlets where the fruits of the ocean were abundantly available. Places like Eigg Mountain were only good as winter hunting grounds. But by 1801 Titus Smith reported in his survey of Nova Scotia forests that scarcity of game in the interior meant that it was “little frequented by the Indians in winter.” Moose were rare, caribou numbers had been reduced by fires that destroyed the “Caribou moss” they fed on, and the beaver were “almost all destroyed,” by trapping for the fur trade.[3] The Mi’kmaq would have understood that they retained the right to use these lands for hunting (“usufruct rights” in English law), but that such rights were not exclusive, so that these lands could be shared with others for similar or other purposes.

There is a kind of natural justice in this idea that you have a right if you can use a piece of land that no-one else is currently using. It is an idea that many of the Highland settlers shared with the Mi’kmaq. While many petitioned and were granted land from the Crown, others for whatever reason, did not. In some cases, the land that they desired had already been granted to absentee landowners. Land grants were often treated by governing parties as political gifts and favours. In the Dominion Land Survey of Western Canada there was a systematic, legal procedure for distributing these favours. A certain percentage of grants was reserved in each surveyed block for the Hudson’s Bay Company and the railway companies. The rest were given to settlers under strict conditions that they actually take up residence and cultivate the land. The hard toil of these people would increase the economic value, not only of their own grants, but of the surrounding grants. When settlers were prosperous enough to buy more land, the non-resident grant holders, having done nothing but wait, were able to sell their grants and convert their abstract possession into money.

|

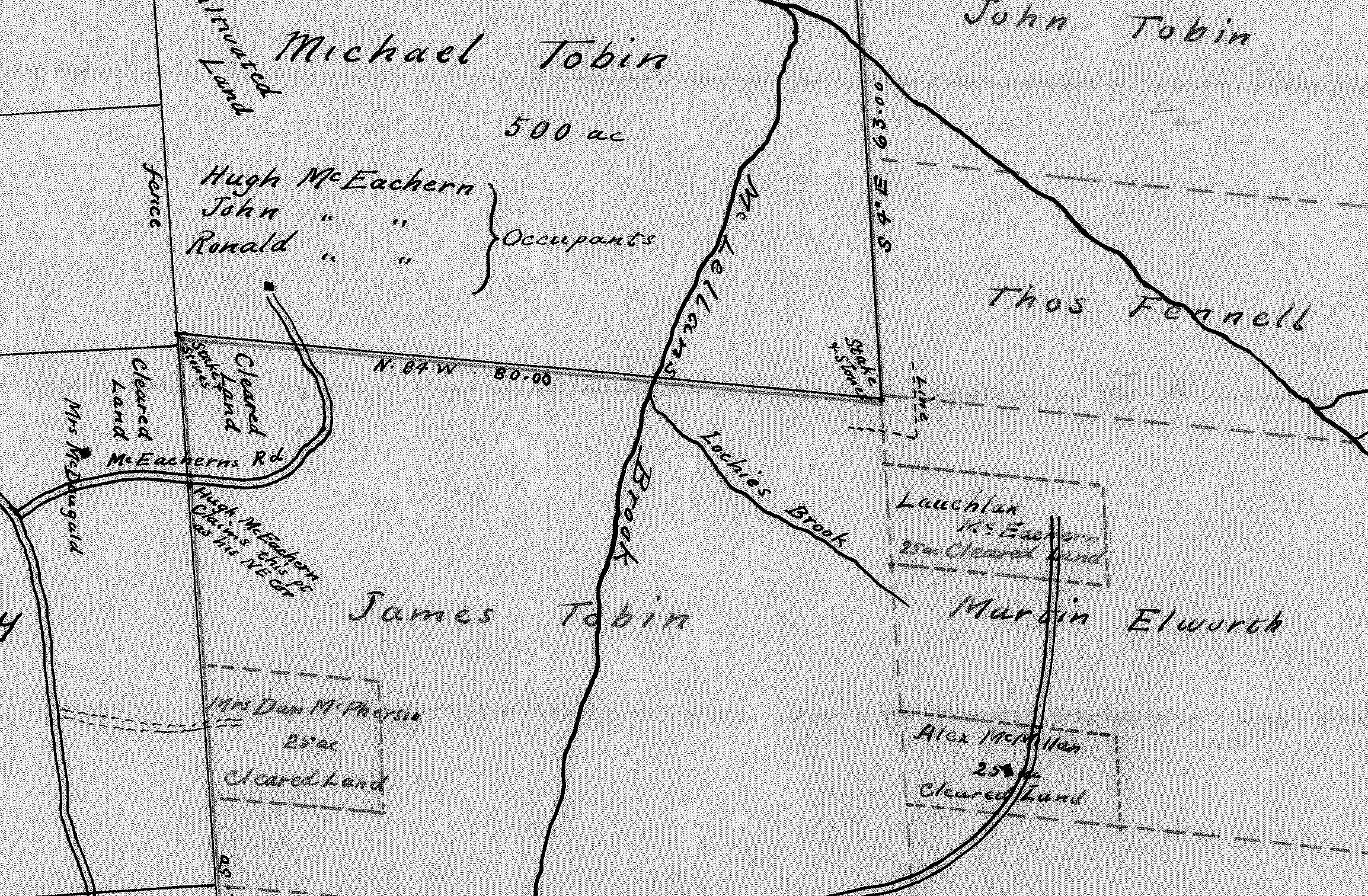

Figure 2 – McKean's Plan of Escheated Lands, 1912 (detail) |

| In this plan you can see how Eigg Mountain settlers have "squatted" on lands granted to absentee owners. In defiance of normal convention the surveyor, Albert McKean, has placed south (towards Brown's Mountain) at the top of the map. |

In giving these gifts the state was in effect transferring the value of the work of those actually on the land to those who merely stood by and watched. Ownership purely for future sale on the expectation of an increase in value is known as “speculation.” In the late 19th century speculation was considered by Canadian legislators to be “injurious” only if anyone could do it. If everyone stood back and waited for the land to increase in value, no-one would be doing the work to produce that value. So the thousands of anonymous immigrants who petitioned for land in Western Canada with the intent of farming were required by law to make improvements or else lose their title. In contrast, in 19th-century Nova Scotia, at least from the evidence of Eigg Mountain, the granting of land seems to have been ad-hoc, haphazard and not tied to meaningful conditions of tenure.[4]

There was no legal distinction between lands that were granted to settlers and those that were granted to speculators on Eigg Mountain, however there did tend to be a difference in the size of grants. Privileged grantees received large tracts in advance of settlement: Rev. Anthony Manseau (501 acres in 1817); William H. Worthy (492 acres, 1817); Joseph Fennell (478 acres, 1817); Rev. A. MacDonald (471 acres, 1817); Rev Edmund Burke (317 acres, 1817). Members of the Tobin family (John, James and Michael) who no doubt carried political weight in Halifax, received a total of 1,708 acres in 6 lots. John Tobin was a Halifax merchant[5] and no doubt the family carried political weight in the province. In contrast to these 400-acre grants, farm lots granted to Irish and Scottish settlers were in the range of 100 to 200 acres. In practice, most farm households did not clear more than about 60 acres and cultivated much less.

Minimal conditions of improvement were stipulated in a standardized land-grant form in the early 1800s. In order to retain title grantees were required within five years to “clear and work” three acres of every 50 acres of arable land or graze 3 “neat cattle” for every 50 acres of “barren” land.[6] However there is no evidence that anyone came to inspect or record whether or not these improvements were undertaken. None of those who were given gifts of large grants appear in the censuses for this area, so they could not have been clearing land or keeping livestock. They may however have taken advantage of what might be termed a “clause for capitalists” in the land grant form. Any grantee with sufficient capital could obtain title by employing for a period of three years “one able hand, for every hundred acres, in cutting wood….” John Tobin was a Halifax merchant, Joseph Fennel a mariner.[7] The timber industry, directed mostly towards shipbuilding, had been booming on the Northumberland coast; prices had recently been protected by a British tariff; and the returns on a particularly fine tree suitable for a mast were impressive.[8] It would make sense that these men were speculating in timber, rather than agricultural development.

The requirement to hire workers had to be fulfilled “within a reasonable time” which could easily have been interpreted by a merchant or his lawyer to mean “when the price (of timber) was right.” There was a further stipulation that had to be fulfilled in order to use the capitalist clause and that was that the land had to be deemed “so rocky or stony as not to be fit for culture or pasture.”[9] Agronomists in the late 20th century categorized the whole of Eigg Mountain in this way,[10] but in the 19th century the potential of the land was an uncertain matter. There was an implicit struggle between competing assessments, with settlers betting their lives and futures on the hope that Eigg Mountain could be made fruitful for agriculture.[11] Whether or not the absentee owners actually engaged in lumbering or profited from it is a matter for further research.[12] However, if their aim was speculative gain through resale, then they likely would have been disappointed. In some cases the land was never sold within the grantee’s lifetime. If these grants were sold, the prices would likely have been trifling.[13]

Legal title may have meant little more than a scrap of paper tucked away for a hundred years in some dusty bureau drawer in Halifax. But these scraps of paper appear to have come into conflict with settlers’ claims to land. The “Cape” MacIsaacs settled on William Worthy’s 500 acres; MacPhersons and MacEacherns took up residence on one of James Tobin’s 500 acre grants; Frasers and MacDonalds claimed portions of land granted, in 1812, to absentee owner James Fleming. In most of these cases, title was never formally transferred from the original grantees to those who actually worked the land.[14] Yet, by the very act of farming these lands settlers were implicitly undermining the absentee grantees only basis for claim by demonstrating that the land was “fit for culture or pasture.”

|

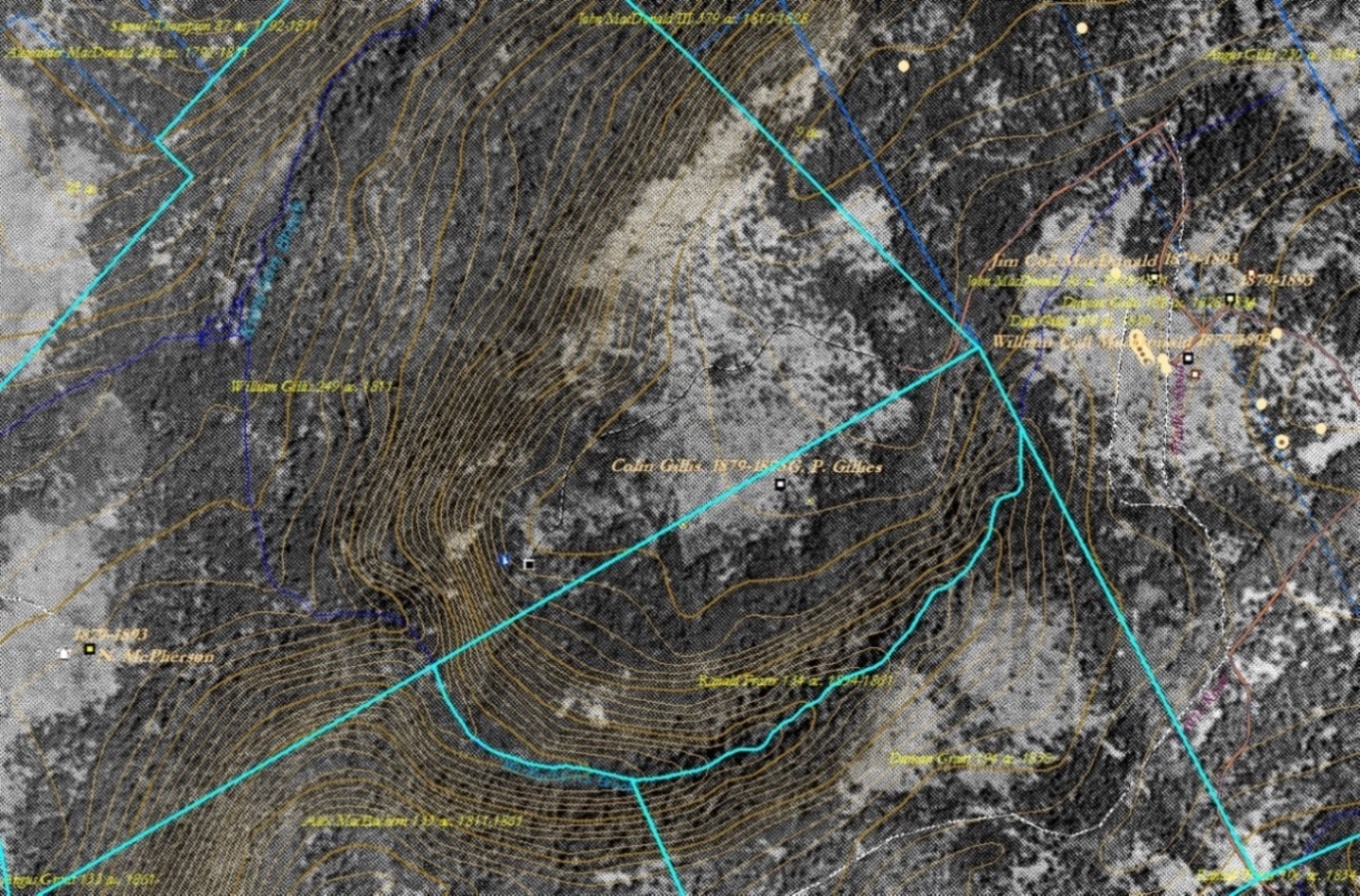

Figure 3 – Property boundaries over a georeferenced aerial photo. |

| Note how the Colin Gillis field crosses boundaries (here highlighted). The tightly-spaced contour lines (tan coloured) indicate the cliff. The boundary between the Duncan Grant and Ranald Fraser grants is very unusual in following a natural feature – in this case a stream at the bottom of a steep gully. Strangely, this natural boundary creates a lot to the north (granted to Ranald Fraser) that would have been unusable.[15] |

“Squatting,” or settling on land to which one had no legal title, was common in Nova Scotia, indeed the Commissioner of Crown Lands, John Spry Morris described it in 1851 as a “constant” problem. He considered it a “very serious evil” mostly because it was annoying and time consuming to be called upon to survey lands piecemeal and after people had set their own de-facto and often haphazard boundaries.[16] A few squatters on Eigg Mountain defined their own property boundaries in contradiction to existing legal boundaries. The Fraser lot is a good example. Here the lines respect features of the land favourable to farming, whereas surveyed lines can often divide natural features of the land in arbitrary fashion. For example there is a little plateau on a spur on the northwest edge of the Mountain. While it is only big enough for one farm it is sliced into two by the boundary line. The southern portion would not be farmable. The northern portion is separated off from more extensive farmlands by a cliff (see Figure 3).

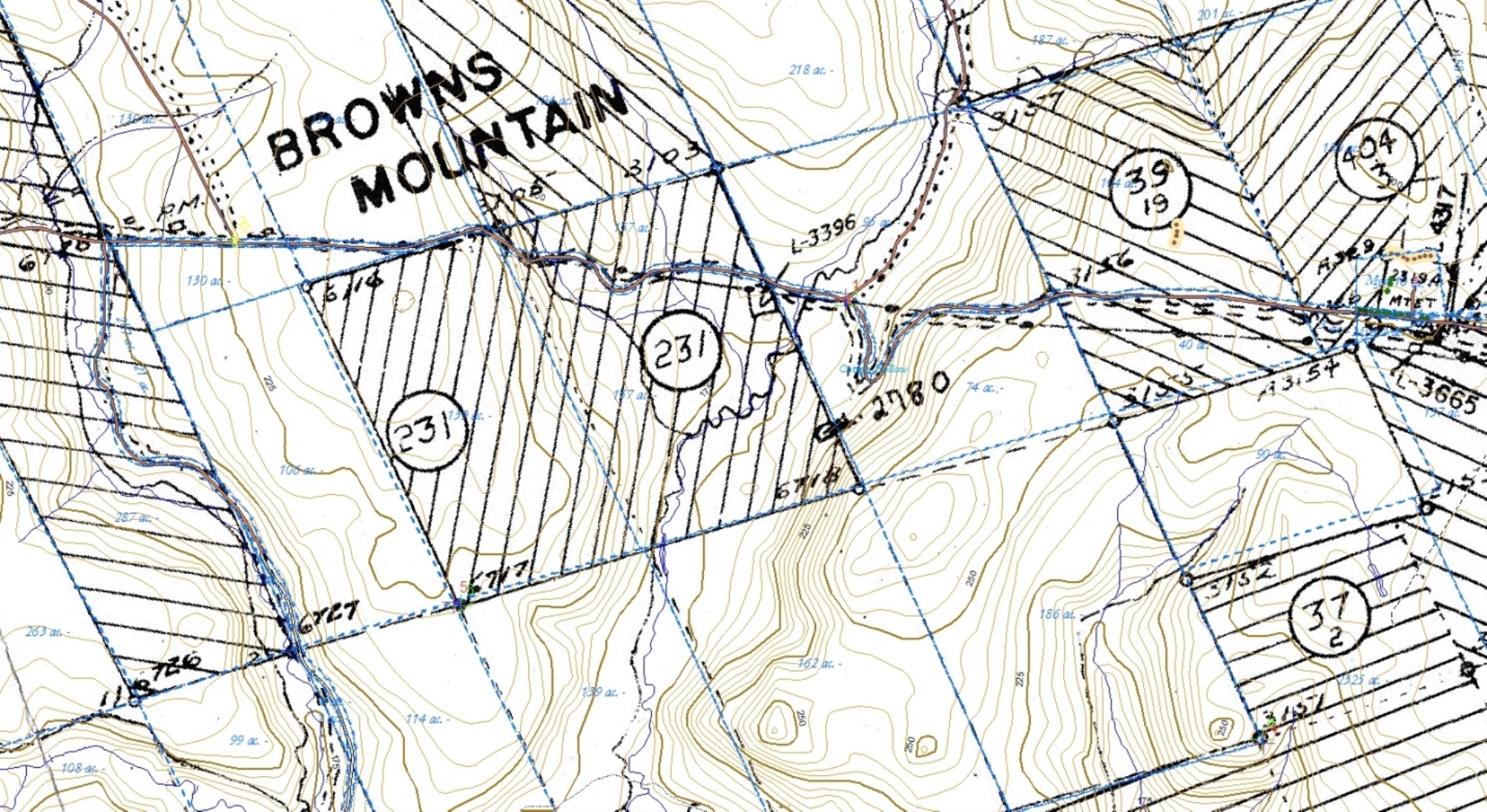

Whoever chose to draw the lines in this way, their logic is now unclear. The first line of lots along the Northumberland Strait conform to a “line-plan” of long, narrow lots oriented perpendicular to the shoreline. This makes sense because everyone benefitted from a small amount of water frontage which was valuable for fishing and transportation. Each strip of land included a level portion close to the shore for fields and an upland portion for woodlot. The next line of lots inland, particularly in the Back Settlement Arisaig, follows a similar pattern. Where there is no water frontage, lots in a line-plan typically front a road – that is only partially true here. The lots south of Eigg Mountain, especially along the Main Road of Browns Mountain, follow a more-or-less regular, rectilinear pattern, more-or-less oriented to the cardinal points (north-south-east-west, see Figure 4). This is a pattern that serves bureaucratic efficiency in surveying and record-keeping and is indifferent to the characteristics of the land. The two patterns seem to collide on the plateau of Eigg Mountain and result in a haphazard arrangement with no discernible logic.

|

Figure 4 – Land Grants Map georeferenced to ArcView map. |

| The Grants Map here had to be rotated about 17º counter-clockwise since the original, instead of being oriented to true north is more-or-less oriented to magnetic north. The only indicator of north on the map is magnetic north for 1949. The grants on Browns Mountain are not-quite regular and not-quite rectangular. Their sides lean about 26º west of true north and their base line is rotated about 17º west of the cardinal points.[17] |

Whether or not settlers’ own lines correspond with legal boundaries, the boundaries defined by use become over time more real. The legal boundary is inscribed in words or lines on paper; the actual boundaries are inscribed on the land by clearings in the forest, by lines of trees or rocks, and by alterations to the structure and composition of the worked-over soil. The best example of a boundary wall is from Brown’s Mountain. For Eigg Mountain examples, beginning with the longest, straightest walls, see Allan MacEachern; the Mooney/Fraser property; Angus Malcolm Fraser; Donald MacMillan; Archie Mor MacDonald; John Smith. The land remembers these boundaries long after the people who made them are gone. In many cases, the legal boundaries are quickly forgotten, or more precisely, the markers that position them decay.

Consider the legal description (Plan B-11-1) for a large parcel of land containing Powers Brook. It starts with a marker made of a wooden stake and a pile of stones. There is no longitude and latitude defined for this spot. From here the document directs the surveyor to follow a compass bearing and measure out a distance using a standard-length chain. Steel chains were subject to wear and stretching and had to be re-checked periodically for accuracy. On uneven, sloping ground typical of Eigg Mountain, chains rarely measured a straight distance since they followed land contours. Chain and compass bearings were the main aids in directing the surveyor to the numerous spots defining the boundaries of the property. Some of the spots are also marked by blazes on trees (e.g. “to ccc 1886 dead beech”) or by stone-piles and stakes. Normally in a “metes and bounds” land description of this type, the names of the property-holders surrounding the property (i.e. the “bounds”) are also described. Here they are missing. The most amazing part of the description is for a line dividing the parcel: “beginning at birch 16” dia., thence S 84 E 93.00 [chains] to fallen maple rampike.” The directions are both imprecise and impermanent. Trees grow (to become wider than 16”) and die; a rampike is an already-dead tree, its bark has fallen off and the wood beneath has turned white, dry and brittle. These “official” markers have long vanished while many of the lines drawn by settlers remain.

Another curious feature of this and most of the other land descriptions in the area is that the documents treat magnetic north as though it were true north. True north does not change, and anyone can find it by locating the North Star. In some places magnetic north is a close approximation to north, but not in Nova Scotia where it is off in the range of 20º - 24º to the west. Worse, the angle between true north and magnetic north, known as declination, changes over time. So the old land descriptions, without telling the reader this, orient all boundaries to a reference point west of north that slowly drifts eastward and westward.[18] In order to overcome this problem, Nova Scotia surveyors were supposed to determine the year of the original survey, consult an historic index of the yearly changes in declination, and then adjust all the compass bearings for any resurvey. This arcane and unnecessarily complex procedure made it difficult for settlers to determine their own boundaries and undoubtedly led to inaccuracies in surveys.

Where the declination is so great, reliance on an uncorrected compass could result in a slightly skewed sense of where north is. That may explain a Nova Scotian tendency that persists to the present, of imagining the province as lying in an east-west direction when in fact that mental image should be rotated an eighth-turn counter-clockwise (see Figures 4 and 5). Confusion between north and west seems occasionally to dog land descriptions.

|

Figure 5 – Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s Map of Nova Scotia (1829) |

| The map is oriented as though the province ran east-west. This odd convention is repeated in the Grants Maps of 1953 (see Figure 4). |

Where settlers were clearly trying to stick to the official lines, it is not surprising that sometimes they got it wrong, or at least were at odds with the often confused surveyors.[19] In the case of the grant to Andrew Mooney, surveys gave contradictory information about how far north or south it was. The Mooneys or maybe the Frasers built their own line in stone at a location not recognized by any of the surveys. I have included these unofficial lines and variants of the survey on the map.[20] The shifting and uncertain boundaries of property make determining who owned what and when sometimes next to impossible.

Yet another difficulty is that settlers often did not communicate with the offices responsible for recording land titles. Many were illiterate and all would have had to travel some distance to the record office. It took three years for Donald Fraser and his wife Mary to register a land transaction to their son Angus. When they did so they signed the document with an “x.” Some, according to Kenton Teasdale, understood the physical possession of the deed to constitute ownership. It made sense on this understanding to transfer title by placing the deed in the hands of the new owner, but without notifying the land office.

There were in a sense two parallel realities about land claims – the one demanded by law and the one practised on the ground. However it was not simply that the state was in command of a clear, unambiguous and legitimate system and that the settlers failed to understand or comply with it. The state’s initial claims to sovereignty were vague and shaky and its grasp on and therefore its ability to control what happened on the ground in terms of land claims was tenuous. Furthermore, state-sanctioned land grants were often unjust, and the boundary lines irrational and poorly suited to the needs of actual settlers.

In other ways the external claims of law and government on Eigg Mountain were weak. “Local” government had existed since 1785, but the County of Sydney was huge until 1835,[21] and even then its legislative reach or capacity to provide local services would have been limited. Road building and maintenance – the bare minimum of municipal service – was probably done by the settlers themselves. These were rocky tracks that barely accommodated a horse-drawn cart.[22] (Even today locals take responsibility for maintaining public roads – it is generally a good idea to take a chainsaw along when travelling on Eigg Mountain.) With no state-provided services before the establishment of the school (possibly late in the 19th century) there can hardly have been much rationale for taxation. The Eigg Mountain people were largely self-governing, relying upon tradition and community to organize their common affairs and settle disputes. Feuds and even murders were dealt with without recourse to police or any legal authorities.[23]